1 Introduction

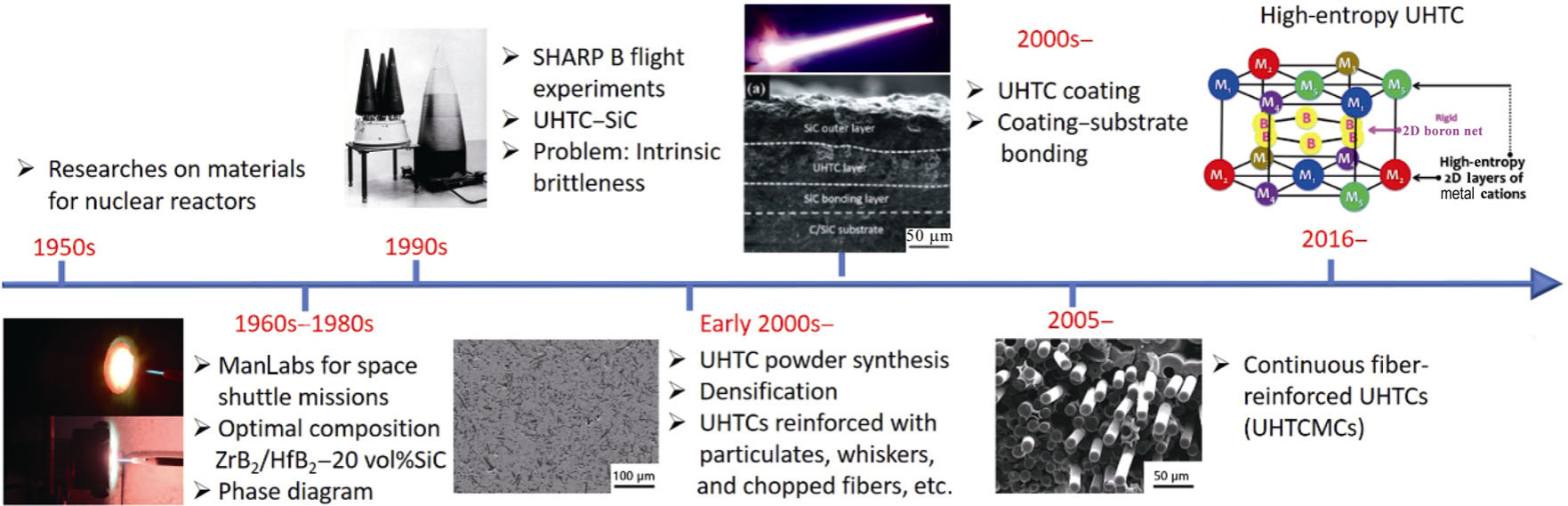

Fig. 1. Historical perspective on research related to ultra-high temperature ceramics and composites. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [10], ©The Author(s) 2022. |

2. Basic properties of UHTCs

| Material | Melting Temperature (°C) | Density (g·cm-3) | CTE, α (10-6·K-1) | Thermal conductivity (W·m-1·K-1) | Hardness (GPa) | Fracture toughness (MPa·m1/2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZrB2 | 3245 | 6.1 | 6.7 | 50-80 | 20-23 | 4-5 |

| HfB2 | 3380 | 11.2 | 6.4 | 40-60 | 25-30 | 4-5 |

| ZrC | 3530 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 20-30 | 25 | 5-6 |

| HfC | 3900 | 12.8 | 6.6 | 20-35 | 24 | 5-6 |

3 Strengthening and toughening methods of UHTCs

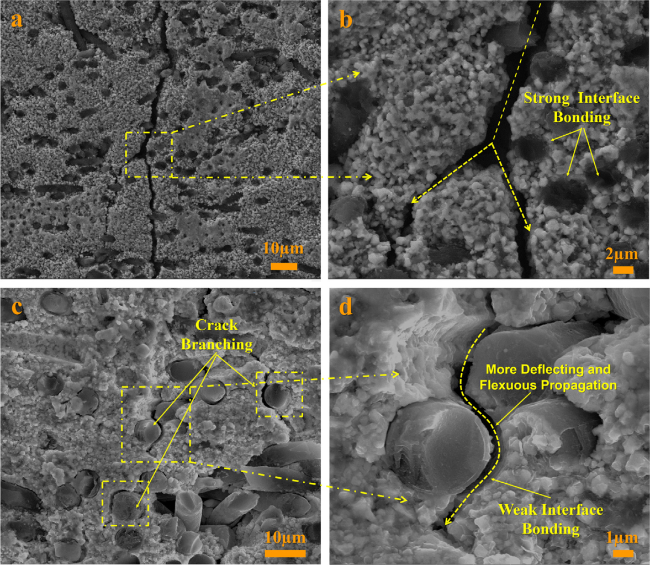

3.1 Particle toughening

3.2 Soft-phase toughening

3.3 Short-cut fiber toughening

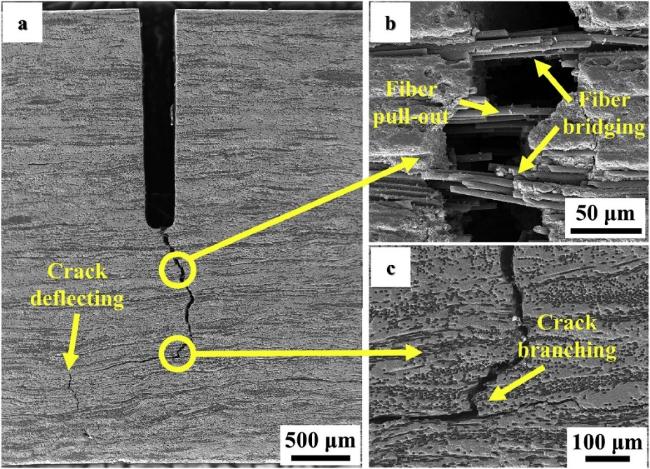

3.4 Continuous fiber toughening

3.5 Design and selection of interface layer

4 Preparation methods of UHTCs and their composites

4.1 Hot pressing sintering and its derivative techniques

4.1.1 Hot pressing sintering technology, HP

4.1.2 Spark plasma sintering technology, SPS

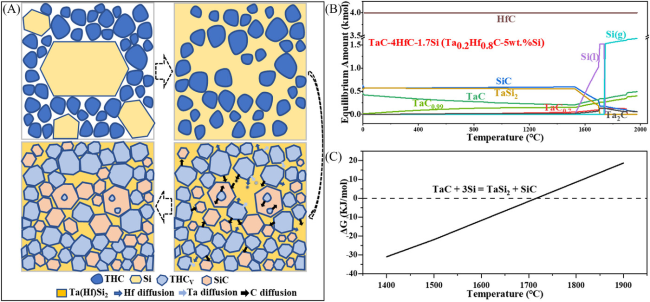

4.1.3 Reactive hot pressing, RHP

Fig. 10. (A) Schematic diagram showing phase and microstructure evolution mechanisms of THS during reactive hot-pressing, (B) thermodynamic equilibrium products of TaC-4HfC-1.7Si reaction system, and (C) standard Gibbs free energy at different temperatures. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [77], © The American Ceramic Society 2023. |

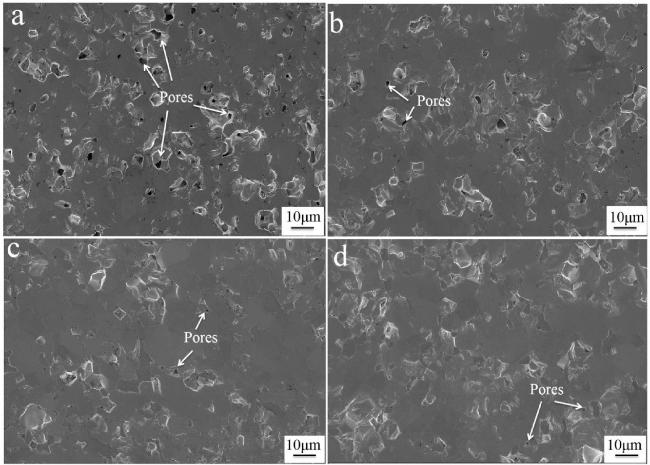

4.1.4 Pressureless sintering, PLS

4.1.5 Nano-infiltration and transient eutectoid, NITE

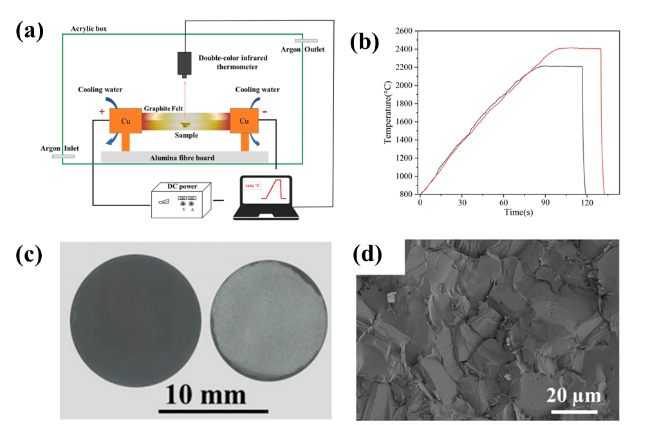

4.1.6 Ultrafast high-temperature sintering, UHS

4.2 Slurry Infiltration, SI

4.2.1 The principles of the slurry infiltration fabrication method

4.2.2 Advantages and disadvantage of the slurry infiltration fabrication method

4.2.3 Future development directions of the slurry infiltration fabrication method

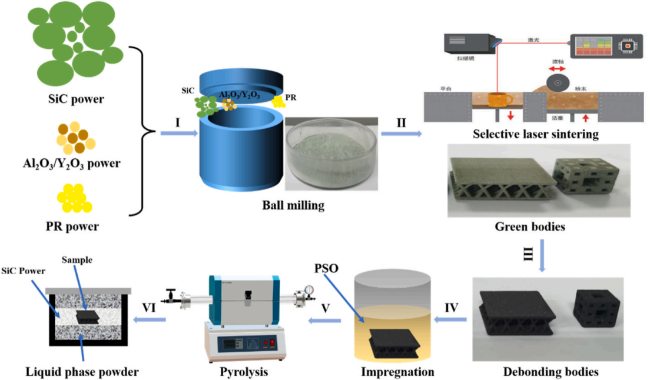

4.3 Precursor infiltration and pyrolysis method, PIP

4.3.1 The basic principles of the PIP method

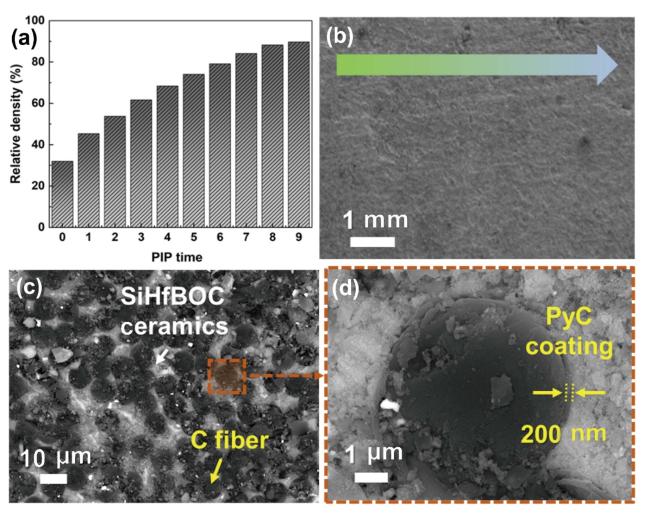

Fig. 14. (a) Density curve of 3D PyC-Cf/SiHfBOC composites with PIP process time, (b) SEM image of 3D PyC-Cf/SiHfBOC composites after 9 PIP process time, (c) BSE image of 3D PyC-Cf/SiHfBOC composites, and (d) high magnification micromorphology of (c). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [101], ©The Author(s) 2023. |

4.3.2 Advantages and disadvantages of the PIP method

4.3.3 Recent advancements in the PIP method

4.4 Reactive melt infiltration technology, RMI

4.4.1 The basic principle of the RMI method

4.4.2 Advantages and disadvantages of the RMI method

4.4.3 Recent advancements in the RMI method

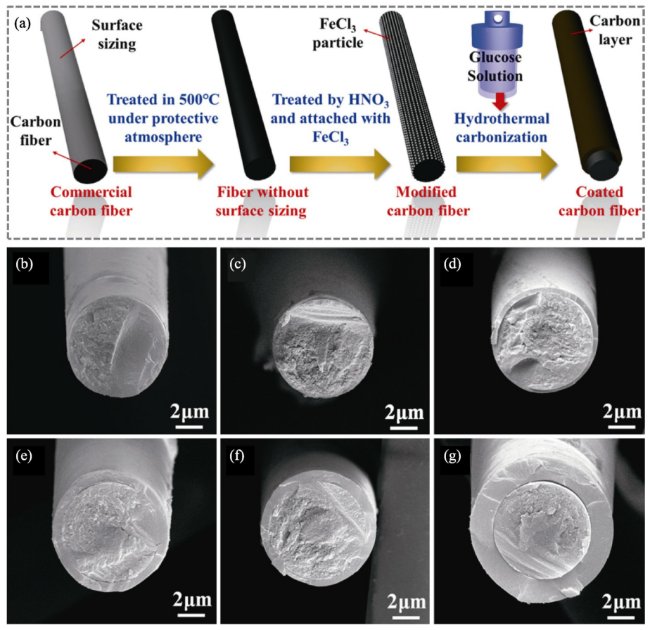

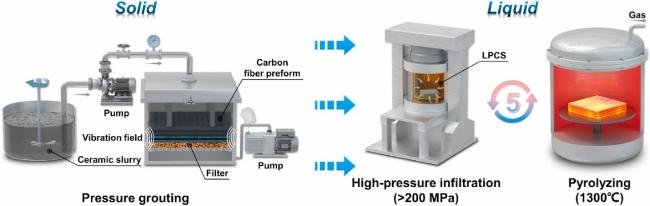

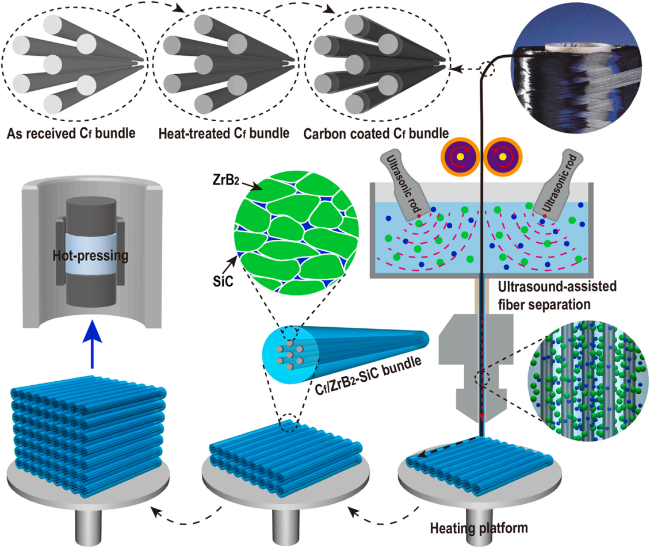

4.5 "Solid-Liquid" combination process

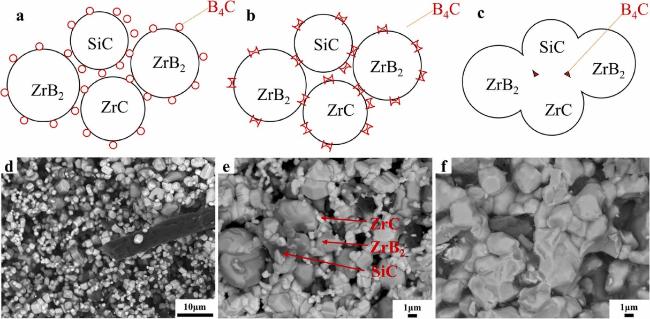

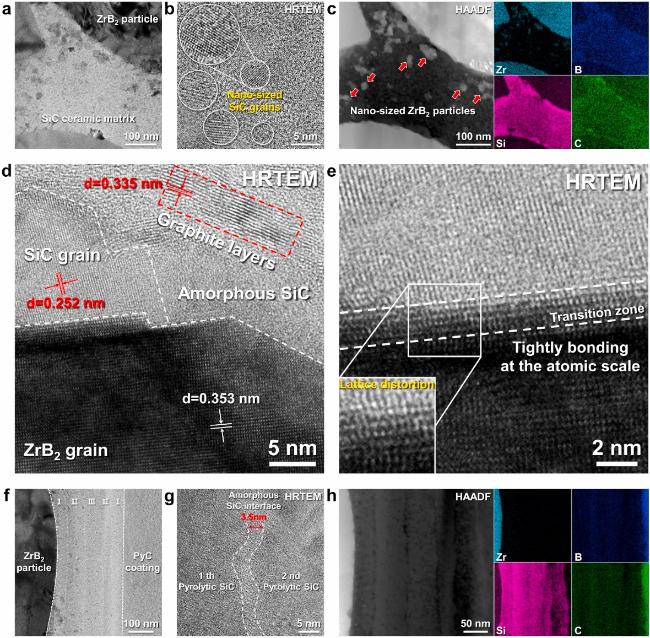

4.5.1 Solid phase: Ultra-high temperature ceramic vibration-assisted slip casting

4.5.2 Liquid phase: silicon carbide precursor high-pressure impregnation and low-temperature pressureless sintering

4.5.3 Research progress of "Solid-Liquid" combination process

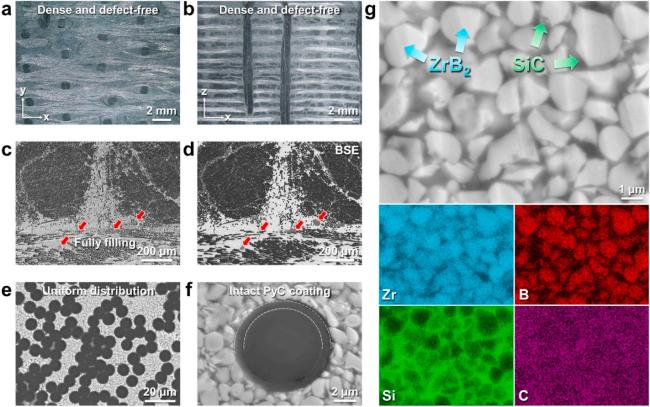

Fig. 19. Macro-and micro-structure of the as-prepared Cf/ZrB2-SiC composite: (a) and (b) surface and cross-section morphologies; (c) ∼ (f) SEM images of cross-section morphology at different magnifications; (g) elemental distribution of the matrix. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [122], © Elsevier 2024. |

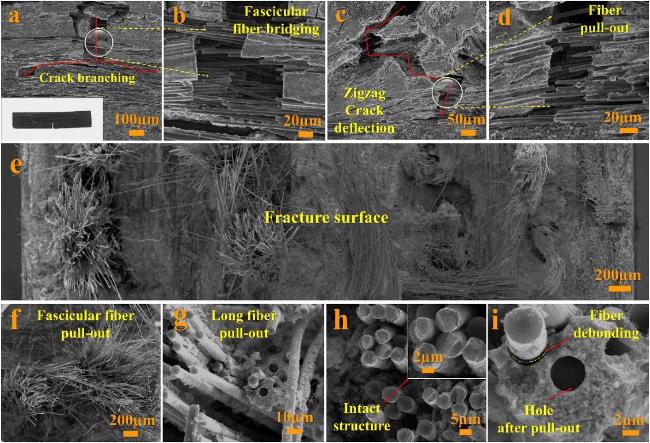

Fig. 20 The microstructures of specimen after mechanical property test: (a) crack branching; (b) fascicular fiber bridging; (c) crack deflection; (d) fiber pull-out; (e) the whole fracture surface morphology; (f) fascicular fiber pull-out; (g) long length fiber pull-out; (h) intact structure of carbon fiber; (i) fiber debonding and hole after pull-out. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [124], © Elsevier 2019. |

4.5.4 Advantages of "Solid-Liquid" combination process

4.5.5 Application prospects and future research directions

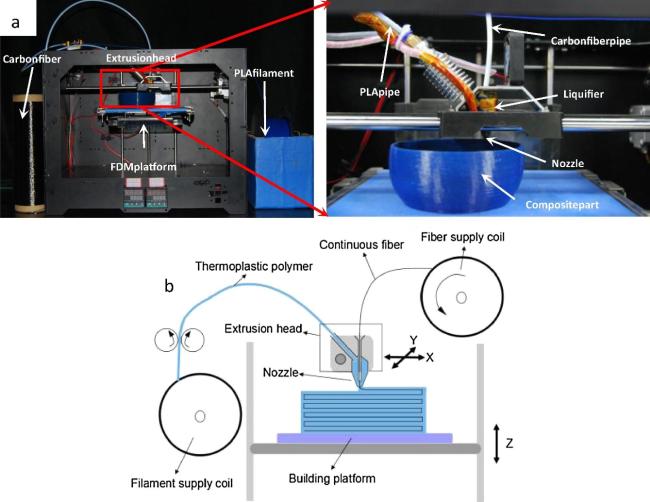

4.6 Additive manufacturing technology, AM

Table 2 Advantages and Disadvantages of Various Fabrication Techniques for UHTCs and Their Composites |

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Future development directions |

|---|---|---|---|

| HP | Simple process, suitable for large-scale production | Stress may be generated during the preparation process. Manufacturing UHTC composites with complex structures is challenging. | Developing new sintering methods and optimizing process parameters. |

| SI | Good compatibility, relatively flexible preparation process, and uniform distribution of ceramic matrix within the fibers | Prone to defects, affecting interfacial bond strength. The preparation cycle is relatively long. | Optimizing slurry formulations and particle distributions to improve the uniformity of matrix distribution, and developing new types of interfacial binders or surface treatment technologies. |

| PIP | Simple process, low cost, suitable for components with complex shapes | Volume shrinkage and cracking are easily induced during the pyrolysis process. The preparation cycle is lengthy, making it difficult to attain full densification. | Developing novel precursor materials, optimizing the pyrolysis process, and precisely designing the interface structure of composite materials. |

| RMI | High preparation efficiency, short cycle time, high densification, suitable for large and complex products | Fibers are susceptible to damage during the infiltration process. | Developing novel melt materials, optimizing the infiltration process, and precisely designing the interface structure. |

| "Solid-Liquid" combination process | Densifies composites at low temperatures, protecting fibers. Ensures even powder distribution for stable performance. | The process is relatively complex, requiring precise control of the solid-to-liquid phase ratio and reaction conditions. | Optimizing the process to enhance material densification and performance, and developing densification techniques suitable for large-scale and complex-shaped components, and validating their feasibility. |

| AM | Offers high flexibility and precision, enabling the manufacture of components with complex structures | Higher equipment costs. Potential for thermal stresses and cracks, which can affect the mechanical properties of the material. | Optimizing process parameters, developing new material systems, and exploring the integration of multiple manufacturing technologies. |

5. Anti-oxidation and ablation behavior and mechanism of UHTCs

5.1 Progress in ablation testing methods

| Method | Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxy-acetylene ablation | Uses oxy-acetylene flame flow as a heat source for ablation erosion, widely used. | Reliable and cost-effective, suitable for rapid screening of UHTCs materials. | Only simulates high-temperature oxidation environments, without considering plasma-material interaction. |

| Oxy-propane ablation | Uses oxy-propane flame flow as a heat source for ablation erosion. | More stable, safer, and lower in cost compared to oxy-acetylene flame. | Lower testing temperature than oxy-acetylene flame, and similarly, the simulated ablation environment is relatively single. |

| Plasma ablation | Forms a plasma beam by ionizing gas to generate high-temperature, high-speed flame impacting the material surface. | High temperature and high heat flux density, better simulating high heat flux environments; customizable heat flux for different ablation environments. | Relatively low plasma flame velocity; simulated environment differs from real-world conditions. |

| Arc-jet wind tunnels | Testing in a continuous open-circuit arc jet wind tunnel, simulating actual operating conditions with arc jet-generated high-temperature, high-speed airflow. | The simulated ablation environment is closer to real-world conditions, high reference value. | High testing costs, long cycles, and difficulty, unsuitable for initial screening. |

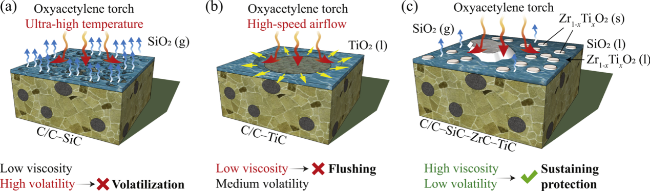

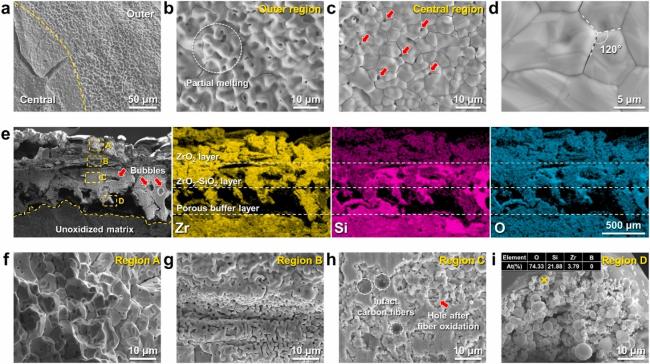

5.2 Oxidation behavior and mechanism of Zr-based UHTCs

| SiC(s) + 1.5O2(g) → SiO2(l) + CO(g) | (1) |

|---|---|

| SiO2(l) + SiC (l) → SiO(s) + CO(g) | (2) |

| SiO2(g) + CO(g) → SiO(s) + CO2(g) | (3) |

| ZrB2(s)+ 2.5O2(g) → ZrO2(s) + B2O3(g) | (4) |

Fig. 25 Schematics of the ablation mechanisms of (a) C/C-SiC, (b) C/C-TiC, and (c) C/C-SiC-ZrC- TiC at 2500 °C. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [159], © Elsevier 2019. |

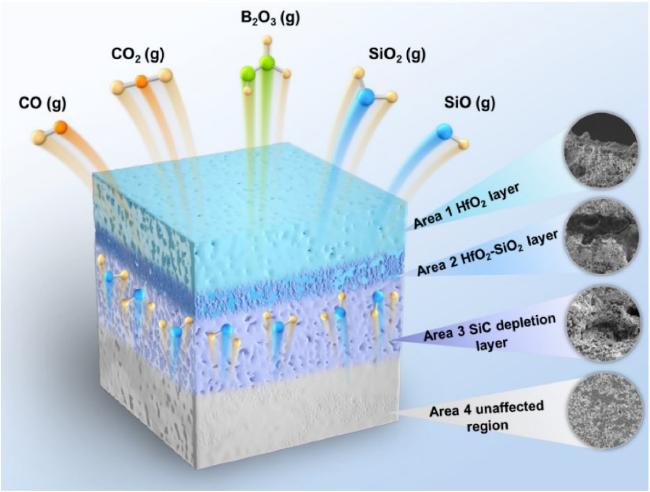

5.3 Oxidation behavior and mechanism of Hf-based UHTCs

| HfB2(s) + 2.5O2(g) → HfO2(s) + B2O3(g) | (5) |

|---|---|

| SiC(s) + 1.5O2 (g) → SiO2 (l) + CO(g) | (6) |

| SiO2 (l) → SiO2 (g) | (7) |

| SiC(s) + O2 (g) → SiO (l) + CO(g) | (8) |

| C(s) + 0.5O2 (g) → CO(g) | (9) |

| C(s) + O2 (g) → CO2(g) | (10) |

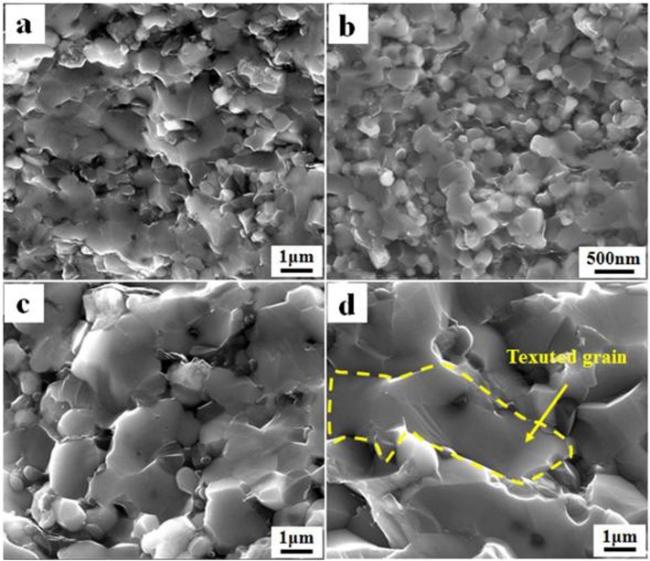

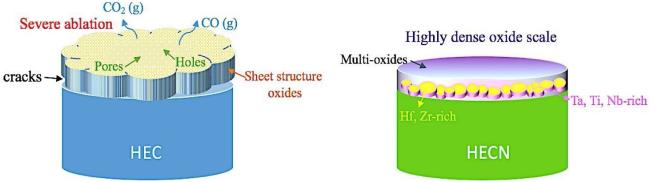

6 High entropy UHTCs and their composites

6.1 Concept and characteristics of high entropy UHTCs

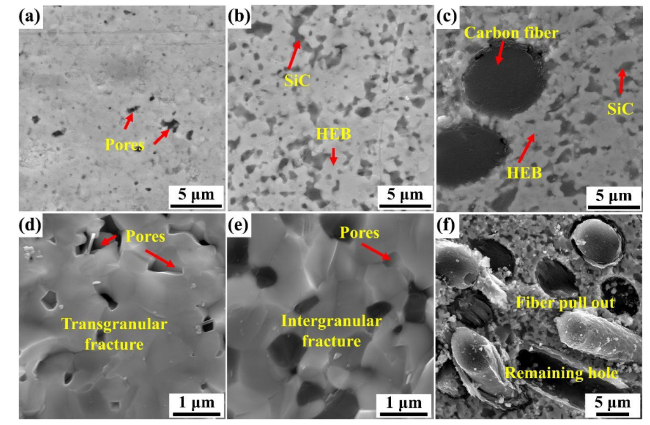

6.2 Research progress on high entropy UHTC composite materials

Fig. 28. Polished and fracture surfaces of (a, d) HEB, (b, e) HEB-SiC, and (c, f) Cf-HEB-SiC. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [178], ©The Author(s) 2024. |

7 Application of UHTCs and their composite materials in extreme environments

Fig. 29. Materials for applications in extreme environments. All images are from Pixabay. |