Introduction

Fig. 1. Structure of N, N Dibutyl aniline (NNDBA). |

Materials and experimental methods

Materials

Inhibitor

Experimental methods

Results and discussions

Gravimetric method

Table 1 Temperature and concentration dependent corrosion rate and inhibition efficiency of mild steel in H2SO4 medium in the presence and absence of NNDBA determined via gravimetric method. |

| Temp. (K) | Conc. of NNDBA (M) | Initial weight Iw (g) | Final weight Fw (g) | Weight loss (g) | IE (%) | Θ | K1⊕10-4 (hr-1 ) | t1/2 (hr) | Cr (mm/y) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298 | 10-1 | 5.2486 | 5.2445 | 0.0041 | 94.8 | 0.948 | 1.30 | 5319.81 | 8.48 |

| 10-3 | 5.9763 | 5.9632 | 0.0131 | 83.4 | 0.834 | 3.66 | 1894.48 | 27.09 | |

| 10-5 | 5.1042 | 5.0854 | 0.0188 | 76.1 | 0.761 | 6.15 | 1126.61 | 38.88 | |

| 10-7 | 6.9352 | 6.9099 | 0.0253 | 67.9 | 0.679 | 6.09 | 1137.50 | 52.32 | |

| Acid | 7.4629 | 7.3841 | 0.0788 | - | - | 17.69 | 391.64 | 162.96 | |

| 308 | 10-1 | 5.8761 | 5.8645 | 0.0116 | 86.4 | 0.864 | 3.29 | 2103.82 | 23.99 |

| 10-3 | 6.4962 | 6.4819 | 0.0143 | 83.3 | 0.833 | 3.67 | 1886.48 | 29.57 | |

| 10-5 | 6.6329 | 6.6097 | 0.0232 | 72.9 | 0.729 | 5.84 | 1186.48 | 47.98 | |

| 10-7 | 5.9756 | 5.9436 | 0.032 | 62.6 | 0.626 | 8.95 | 774.23 | 66.18 | |

| Acid | 7.3616 | 7.2761 | 0.0855 | - | - | 19.47 | 355.86 | 176.81 | |

| 318 | 10-1 | 5.9672 | 5.9295 | 0.0377 | 85.5 | 0.855 | 10.57 | 655.93 | 77.96 |

| 10-3 | 6.883 | 6.8332 | 0.0498 | 80.8 | 0.808 | 12.10 | 572.50 | 102.99 | |

| 10-5 | 6.9231 | 6.8356 | 0.0875 | 66.2 | 0.662 | 21.20 | 326.84 | 180.95 | |

| 10-7 | 6.463 | 6.3487 | 0.1143 | 55.9 | 0.559 | 29.74 | 232.98 | 236.37 | |

| Acid | 7.0705 | 6.8113 | 0.2592 | - | - | 62.26 | 111.31 | 536.02 | |

| 328 | 10-1 | 6.8435 | 6.7953 | 0.0482 | 84.1 | 0.841 | 11.78 | 588.17 | 99.68 |

| 10-3 | 5.9748 | 5.8689 | 0.1059 | 65.1 | 0.651 | 29.81 | 232.46 | 219.00 | |

| 10-5 | 5.8795 | 5.7479 | 0.1316 | 56.7 | 0.567 | 37.74 | 183.65 | 272.15 | |

| 10-7 | 5.3298 | 5.1887 | 0.1411 | 53.5 | 0.535 | 44.73 | 154.94 | 291.79 | |

| Acid | 7.6199 | 7.3162 | 0.3037 | - | - | 67.80 | 0.0102 | 628.05 |

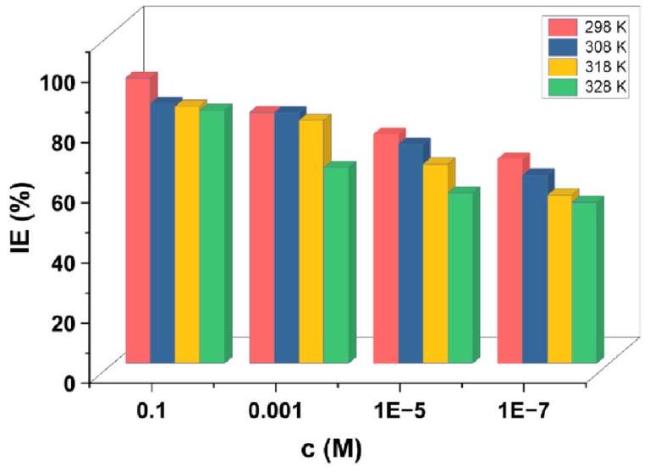

Fig. 2. Effect of NNDBA concentration on corrosion protection performance of mild steel at all studied temperatures. |

Kinetic Study

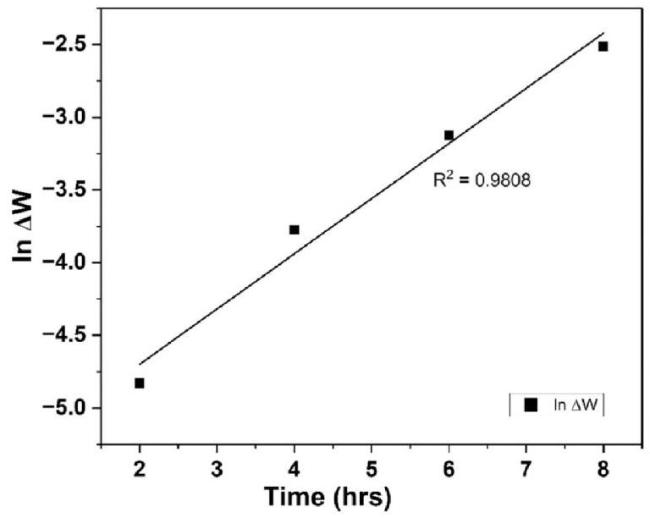

Table 2 Time-dependent mass depletion data for mild steel corrosion in H2SO4 solution. |

| Time (hrs) | Initial weight Iw(g) | Final weight Fw(g) | Weight loss in H2SO4Δ W( g) | ln(ΔW/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 6.3940 | 6.3860 | 0.0080 | -4.83 |

| 4 | 7.1260 | 7.1030 | 0.0230 | -3.77 |

| 6 | 7.0490 | 7.0050 | 0.0440 | -3.12 |

| 8 | 6.8450 | 6.7640 | 0.0810 | - 2.51 |

Fig. 3. Time-dependent corrosion behavior of mild steel in H2SO4. |

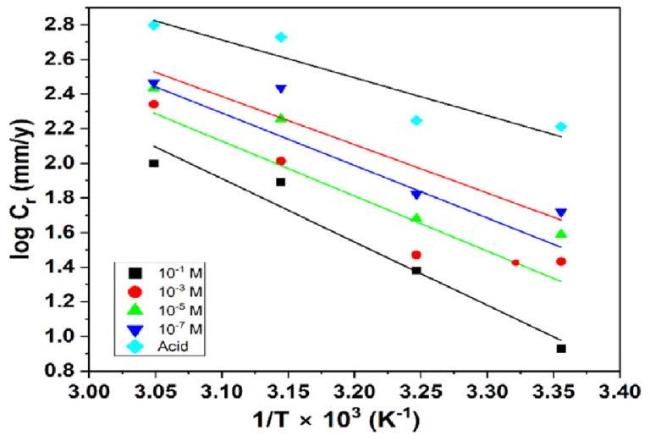

Energy of Activation

Fig. 4. Temperature dependence of corrosion rate: logCr vs. 1/T for mild steel in H2SO4 medium in the presence and absence of NNDBA. |

Table 3 Energy of activation (Ea ) for mild steel corrosion in H2SO4 medium in the presence and absence of NNDBA. |

| S. No. | Concentration (M) | Ea(kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10-1 | 70.04 |

| 2 | 10-3 | 60.71 |

| 3 | 10-5 | 58.09 |

| 4 | 10-7 | 53.49 |

| 5 | Acid | 41.84 |

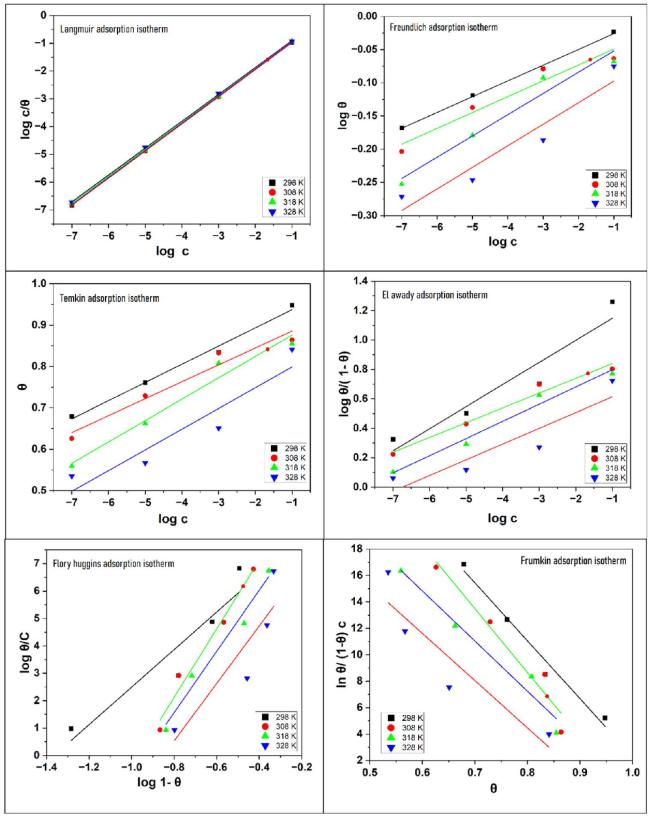

Adsorption isotherm

Thermodynamic Parameters and their Implications

Fig. 5. Different adsorption isotherms for mild steel in H2SO4 medium in the presence and absence of NNDBA (a) Langmuir, (b) Freundlich, (c) Temkin, (d) ElAwady, (e) Flory-Huggins, and (f) Frumkin adsorption isotherm. |

Table 4 Analysis of adsorption behavior using different isotherm models. |

| Isotherm | Isotherm Equations | Temp. (K) | Equation | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | | 298 | y=0.9763x+0.0023 | 1 |

| 308 | y=0.9761x+0.0253 | 1 | ||

| 318 | y=0.9680x+0.0200 | 1 | ||

| 328 | y=0.9675x+0.0651 | 0.9999 | ||

| Freundlich | | 298 | y=0.0237x-0.0023 | 0.9963 |

| 308 | y=0.0239x-0.0253 | 0.9430 | ||

| 318 | y=0.0320x-0.0200 | 0.9588 | ||

| 328 | y=0.0325x-0.0651 | 0.9188 | ||

| Temkin | | 298 | y=4.4x+98.15 | 0.9903 |

| 308 | y=4.09x+92.66 | 0.9552 | ||

| 318 | y=5.17x+92.78 | 0.9676 | ||

| 328 | y=5.01x+84.89 | 0.8871 | ||

| Flory-Huggins | | 298 | y=6.8517x+9.3482 | 0.8874 |

| 308 | y=12.501x+12.123 | 0.9779 | ||

| 318 | y=11.166x+10.501 | 0.9769 | ||

| 328 | y=10.479x+8.9185 | 0.8040 | ||

| El-Awady | | 298 | y=0.1502x+1.2984 | 0.9413 |

| 308 | y=0.1003x+0.9398 | 0.9753 | ||

| 318 | y=0.1168x+0.9144 | 0.9790 | ||

| 328 | y=0.1071x+0.7213 | 0.8473 | ||

| Frumkin | | 298 | y=-43.807x+46.103 | 0.9771 |

| 308 | y=-48.207x+47.232 | 0.9480 | ||

| 318 | y=-37.939x+37.595 | 0.9610 | ||

| 328 | y=-35.748x+33.068 | 0.8531 |

Table 5 Thermodynamic insights from the Langmuir adsorption isotherm at all studied temperatures. |

| Temp (K) | Kads(M-1) | | | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298 | 0.995 | -9.9 | -3.4 | 21.95 |

| 308 | 0.943 | -10.1 | 21.88 | |

| 318 | 0.955 | -10.5 | 22.33 | |

| 328 | 0.861 | -10.6 | 21.79 |

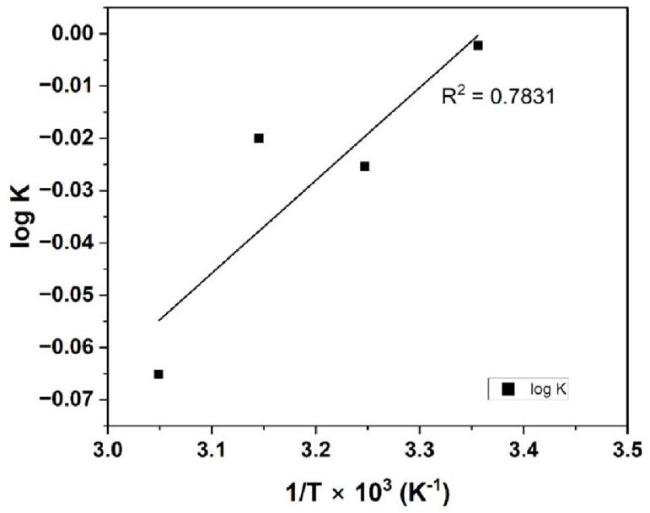

Fig. 6. Temperature dependence of adsorption equilibrium constant: logKadsvs.1/T. |

Fig. 7. Cathodic and anodic polarization run via PDP studies for various concentrations of H2SO4 in the presence and absence of NNDBA at 298 K. |

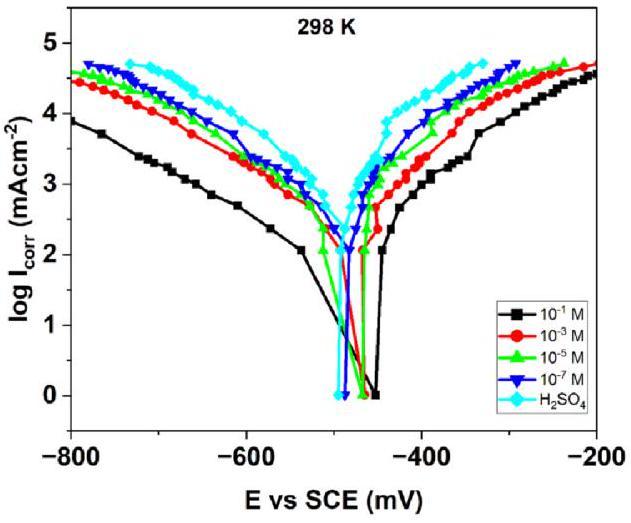

Potentiodynamic polarization studies (PDP)

Table 6 Corrosion current and inhibition efficiency for mild steel in H2SO4 medium in the presence and absence of NNDBA determined via PDP studies at 298 K. |

| Concentration (M) | - Ecorr (mV) | βc (mV/dec) | βa (mV/dec) | Icorr (mA/cm2 ) | IE (%) | θ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-1 | 500.0 | 172.8 | 100.0 | 0.0692 | 94.2 | 0.942 |

| 10-3 | 476.9 | 138.5 | 76.9 | 0.1514 | 87.4 | 0.874 |

| 10-5 | 492.3 | 138.5 | 100.0 | 0.2818 | 76.5 | 0.765 |

| 10-7 | 493.1 | 117.3 | 78.8 | 0.3311 | 72.5 | 0.725 |

| Acid | 465.8 | 106.7 | 120.0 | 1.2021 | - |

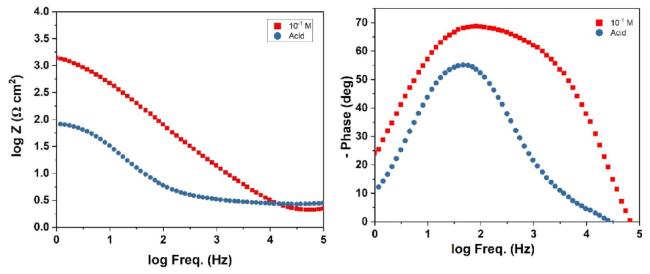

Fig. 8. Bode plot of mild steel in H2SO4 and in 10-1M NNDBA at 298 K. |

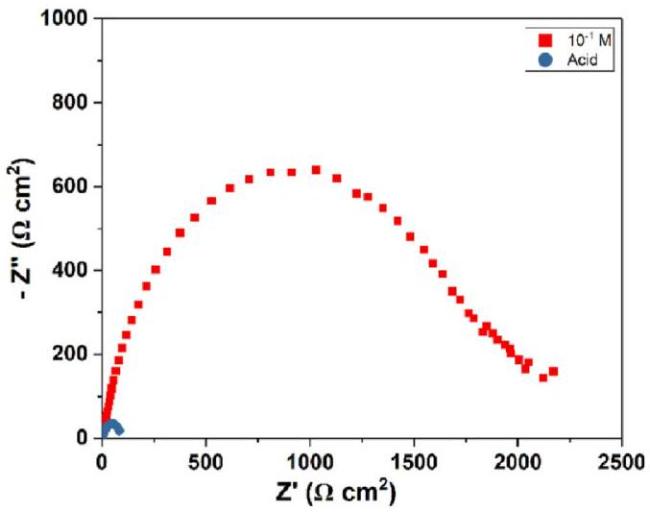

Fig. 9. Nyquist plot of mild steel in H2SO4 and in 10-1 M NNDBA at 298 K. |

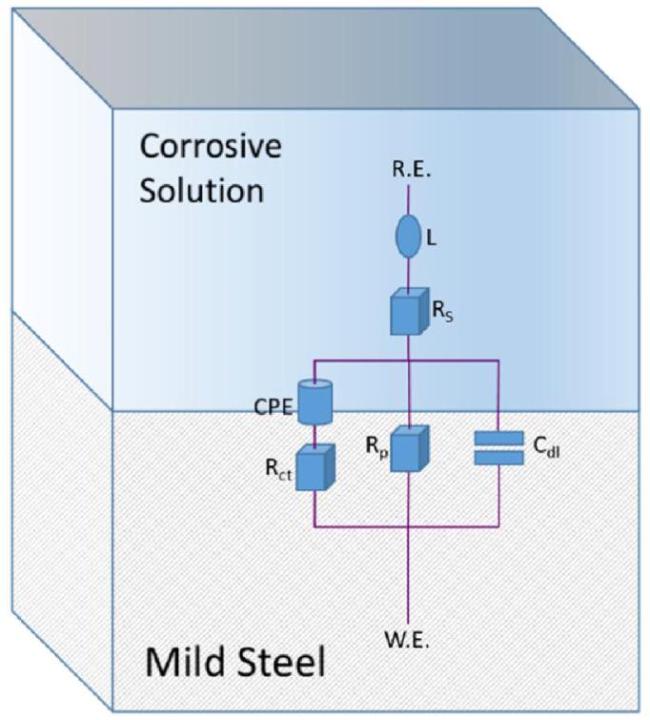

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS)

Fig. 10. Equivalent Circuit. |

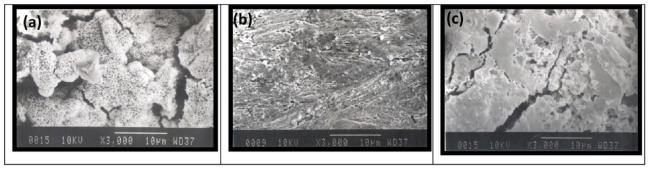

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Table 7 Electrochemical Impedance parameters for mild steel in H2SO4 medium in the presence and absence of NNDBA at 298 K. |

| Compound | Rs (Ω/cm2 ) | Rp(Ω/cm2) | Rct (Ω/cm2 ) | fmax (Hz) | CPE (μS.sncm- 2 ) | n | Cdl(μF/cm2) | IE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NNDBA | 2.218 | 2171 | 2168.78 | 1.74 | 74.92 | 0.7321 | 421.96 | 96.32 |

| 24HSO | 2.809 | 82.43 | 79.621 | 5.49 | 172.5 | 0.9515 | 364.28 | - |

Fig. 11. Scanning electron micrograph of mild steel in (a) 0.5H2SO4 (b) 10-1 M NNDBA in H2SO4 (c) 10-7 M NNDBA in H2SO4 at 3000 magnifications. |

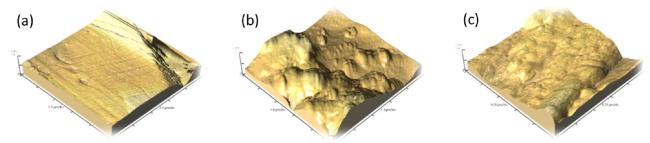

Fig. 12. AFM of (a) plain mild steel specimen, (b) mild steel specimen in the 0.5H2SO4 solution (c) mild steel specimen in presence of 10-1MNNDBAin H2SO4. |

Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

Quantum chemical studies

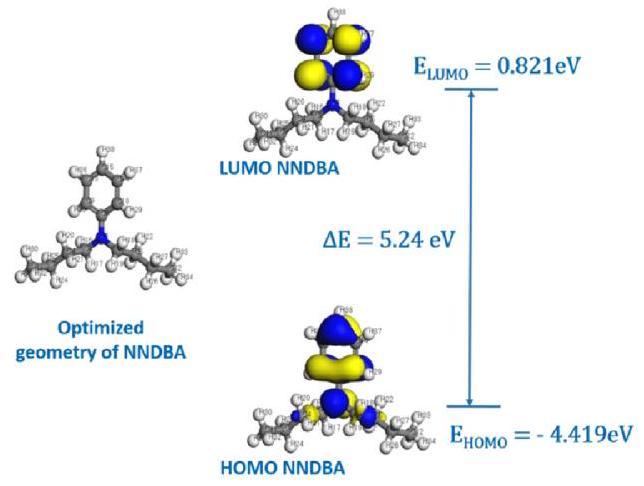

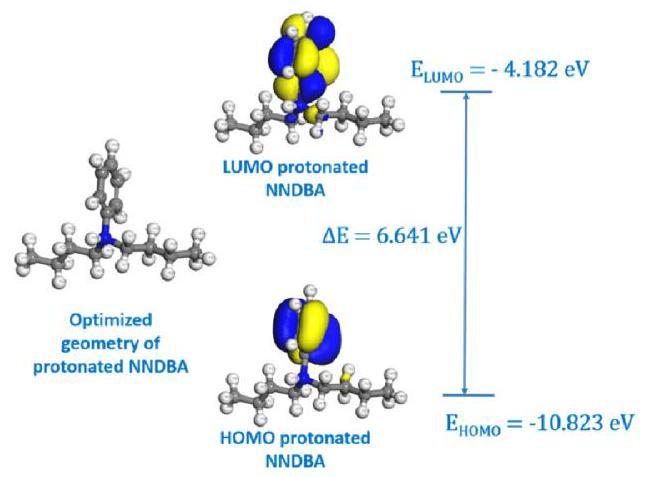

Relation between inhibition efficiency and FMO energies

Fig. 13. Optimized geometry of NNDBA with HOMO and LUMO distributions and their corresponding energy levels. |

Fig. 14. Optimized geometry of protonated NNDBA with HOMO and LUMO distributions and their corresponding energy levels. |

Relation between electronic parameters and type of adsorption

Relation between ΔN and inhibition mechanism

Relation between dipole moment & efficacy of NNDBA

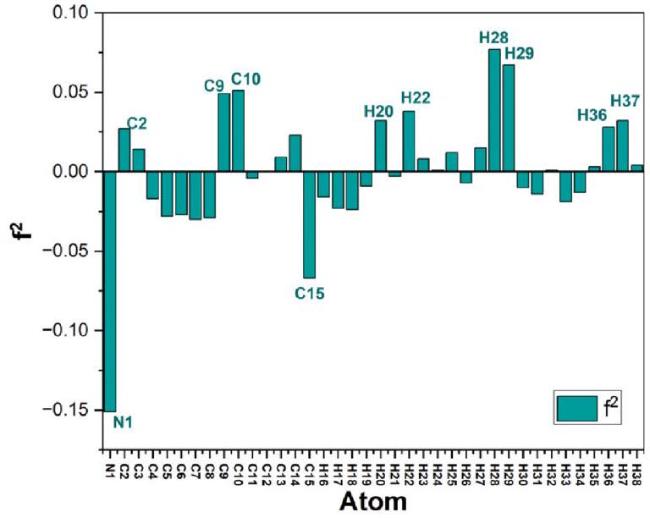

Condensed fukui function

Table 8 Fukui functions (f*,f, and f2 ) for atoms of NNDBA. |

| Atom | f+ | f | f2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | -0.001 | 0.15 | -0.151 |

| C2 | -0.02 | -0.047 | 0.027 |

| C3 | -0.027 | -0.041 | 0.014 |

| C4 | -0.022 | -0.005 | -0.017 |

| C5 | -0.028 | 0 | -0.028 |

| C6 | -0.006 | 0.021 | -0.027 |

| C7 | -0.025 | 0.005 | -0.03 |

| C8 | -0.024 | 0.005 | -0.029 |

| C9 | 0.096 | 0.047 | 0.049 |

| C10 | 0.098 | 0.047 | 0.051 |

| C11 | -0.01 | -0.006 | -0.004 |

| C12 | -0.008 | -0.008 | 0 |

| C13 | 0.062 | 0.053 | 0.009 |

| C14 | 0.068 | 0.045 | 0.023 |

| C15 | -0.006 | 0.061 | -0.067 |

| H16 | 0.022 | 0.038 | -0.016 |

| H17 | 0.035 | 0.058 | -0.023 |

| H18 | 0.017 | 0.041 | -0.024 |

| H19 | 0.042 | 0.051 | -0.009 |

| H20 | 0.02 | -0.012 | 0.032 |

| H21 | 0.026 | 0.029 | -0.003 |

| H22 | 0.023 | -0.015 | 0.038 |

| H23 | 0.031 | 0.023 | 0.008 |

| H24 | 0.023 | 0.022 | 0.001 |

| H25 | 0.017 | 0.005 | 0.012 |

| H26 | 0.019 | 0.026 | -0.007 |

| H27 | 0.018 | 0.003 | 0.015 |

| H28 | 0.109 | 0.032 | 0.077 |

| H29 | 0.104 | 0.037 | 0.067 |

| H30 | 0.001 | 0.011 | -0.01 |

| H31 | 0.02 | 0.034 | -0.014 |

| H32 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.001 |

| H33 | -0.003 | 0.016 | -0.019 |

| H34 | 0.021 | 0.034 | -0.013 |

| H35 | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.003 |

| H36 | 0.094 | 0.066 | 0.028 |

| H37 | 0.096 | 0.064 | 0.032 |

| H38 | 0.084 | 0.08 | 0.004 |

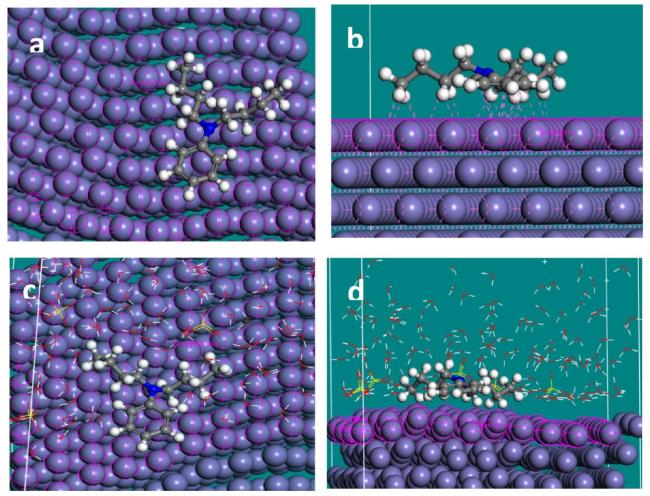

Molecular dynamics simulation

Fig. 15. Bar graph representing the Fukui functions (f*,f, and f2 ) for individual atoms of NNDBA. |

Table 9 Outputs calculated by the Monte Carlo simulation for adsorption of NNDBA, on Fe (110). |

| Parameter | Value (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|

| Interaction energy | -123.11 |

| Binding energy | 123.11 |

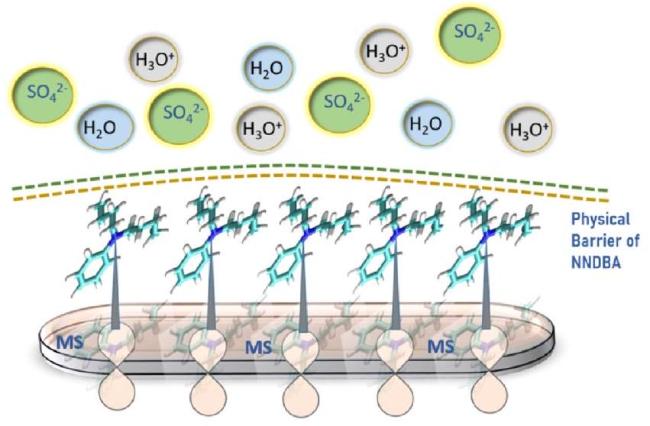

Proposed mechanism

Fig. 16. MD simulation captures in (a) top view of adsorbed NNDBA molecule on mild steel surface (b) front view of interactions between NNDBA and mild steel (c) top view of adsorbed NNDBA molecule on mild steel in presence of H2O and H2SO4 (d) top view of adsorbed NNDBA molecule on mild steel in presence of H2O and H2SO4. |

Table 10 Comparative Overview of NNDBA and Structurally Related Corrosion Inhibitors. |

| Inhibitor | IE (%) | Metal | Media | Adsorption Isotherm | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-Methyl Formanilide | 83.1 | Mild steel | H2SO4 | El-Awady adsorption | [36] |

| (E)-N(2-Chlorobenzylidene)-2-Fluorobenzenamine and | 89.7 | Mild Steel | HCl | Langmuir | [93] |

| (E)-N(2-Chlorobenzylidene) - 3-Chloro - 2-Methylbenzenamine | 85.6 | ||||

| (Z) - 3-(1-(2-(4-amino - 5-mercapto - 4H-1,2,4-triazol - 3-yl) hydrazono)ethyl) - 2 H -chromen - 2-one | 86.1 | Carbon Steel | 1 M HCl | Langmuir | [94] |

| 5 -imino - 1,2,4-dithiazolidine-3-thione (IDTT) | 86.5 | Mild steel | 1 M HCl | Langmuir | [95] |

| 1-((8-hydroxyquinolin - 5-yl)methyl)urea | 87.3 | Carbon Steel | 1 M HCl | Langmuir | [96] |

| (E) - 3-(2-(benzofuran-2-yl)vinyl)quinoxalin-2(1 H)-one | 89.6 | Mild Steel | 1 M HCl | Langmuir | [97] |

| d toluene-2,4-diisocyanate-4-(1Himidazole-ly) aniline (TDIA) | 89.99 | Stainless Steel 304 L | 1MHCl+3.5%NaCl | Langmuir | [98] |

| 4-methyl-1-Phenyl-3-(p-tolyldiazenyl) -2,3-dihydro-1H-pyrrol-2-ol (MPTHP) | 90.6 | N - 80 Steel | 10%HCl | Langmuir | [99] |

| (2-benzoyl-4-nitro-N-[(1H-pyrazol-1-yl)methyl]aniline (BNPMA)) | 93.2 | Carbon Steel | 1 M HCl | Langmuir | [100] |

| 4,6-bis(3,5-dimethyl-1 H-pyrazol - 1-yl)-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine | 93.6 | Carbon Steel | 0.25 M H2SO4 | Frumkin | [101] |

| N, N-dibutyl aniline (Our Result) | 94.2 | Mild Steel | 0.5 M H2SO4 | Langmuir | Our result |

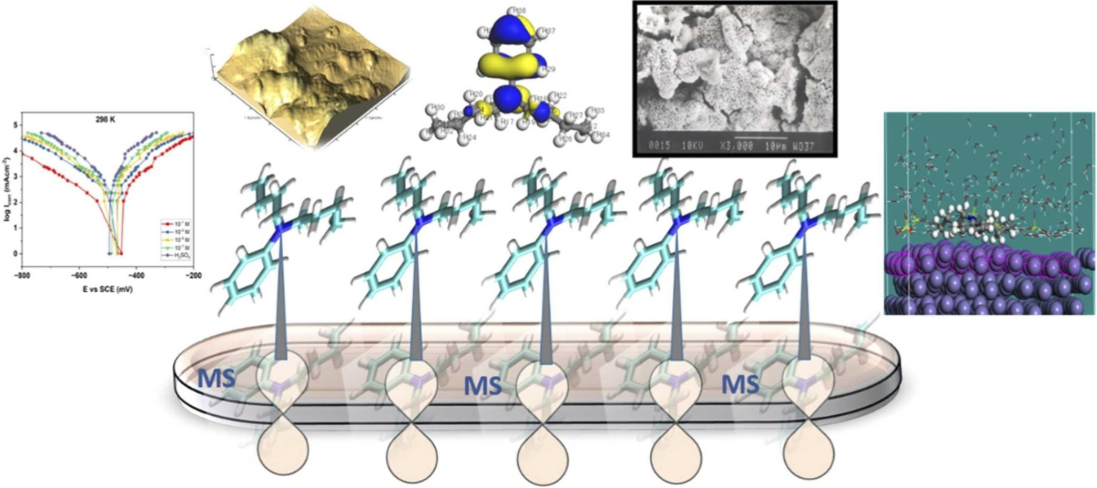

Fig. 17. Visualization of interaction between NNDBA and mild steel (MS) surface. |