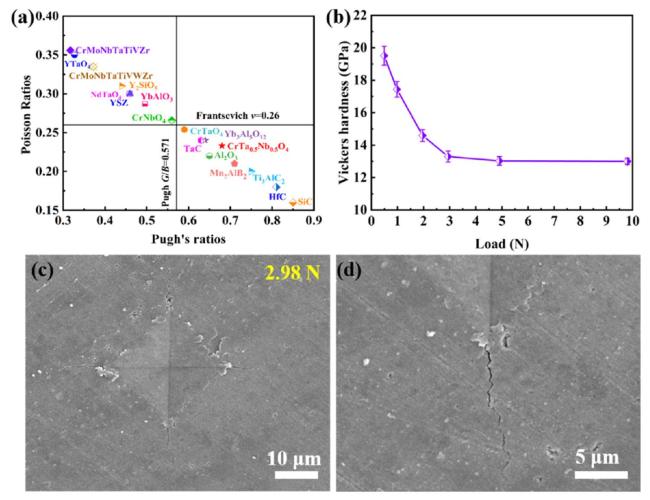

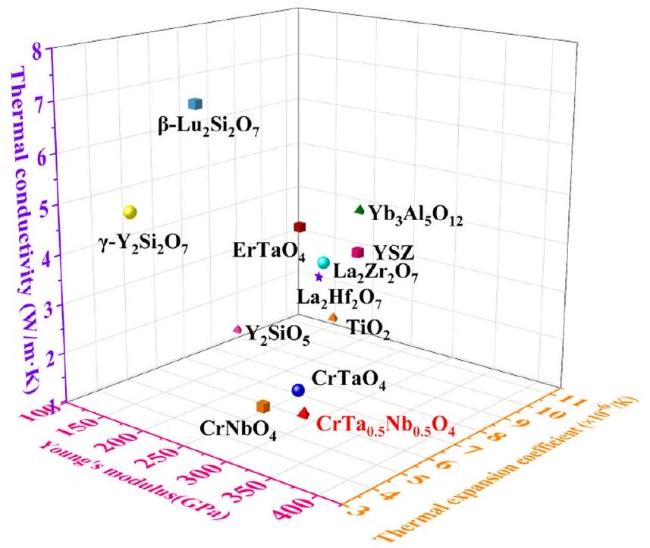

In terms of mechanical properties, the Vickers hardness of CrTa

0.5Nb

0.5O

4 is 13.01±0.20GPa, indicating a 6.6% increase compared to

${\mathrm{C}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{T}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{O}}_{4}\left(\right(12.20\pm 0.44\mathrm{G}\mathrm{P}\mathrm{a})$ and a 27.5% increase compared to CrNbO

4(10.20±0.58GPa). The fracture toughness of CrTa

0.5Nb

0.5O

4 is 2.07±0.017MPa⋅m

1/

2, representing a 10.7% increase over

${\mathrm{C}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{T}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{O}}_{4}\left(1.87\pm 0.074\mathrm{M}\mathrm{P}\mathrm{a}\cdot {\mathrm{m}}^{1}/{ }^{2}\right)$ and a 33.1% increase over

${\mathrm{C}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{N}\mathrm{b}\mathrm{O}}_{4}\left(1.54\pm 0.124\mathrm{M}\mathrm{P}\mathrm{a}\cdot {\mathrm{m}}^{1}/{ }^{2}\right)$. Based on microstructure analyses presented

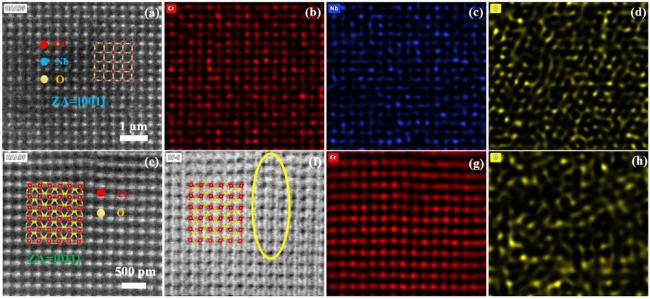

Fig. 5, it is proposed that the primary strengthening mechanisms are attributed to solid solution strengthening and dispersion strengthening. The solid solution strengthening in CrTa

0.5Nb

0.5O

4 is primarily attributed to lattice distortion induced by the differences in atomic radius and electronegativity among

Cr,Nb, and Ta. The differences in atomic properties among

Cr,Nb, and Ta constitute the core origin triggering solid-solution strengthening. On one hand, there exist significant distinctions in their ionic sizes: Cr

3+ has a radius of approximately 0.62Å, while both Nb

5+(≈0.69Å) and Ta

5+(≈0.64Å) are larger than Cr

3+. When Nb

5+ and Ta

5+ substitute for Cr

3+ in the lattice, their larger ionic sizes force the surrounding lattice to undergo local tensile deformation, forming inhomogeneous strain fields. On the other hand, there is a charge difference of +3 versus +5 between Cr

3+ and Nb

5+/Ta

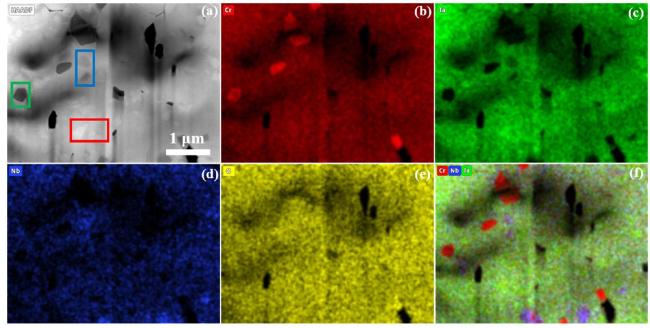

5+. This charge imbalance induces perturbations in the local electrostatic field, further exacerbating lattice irregularities. The lattice strain fields resulting from size mismatch and the electrostatic perturbations caused by charge differences collectively form a "composite resistance field" that hinders dislocation motion. When the material undergoes plastic deformation under external forces, the migration of dislocations (as carriers of lattice slip) is subjected to mechanical obstruction from the strain fields. Meanwhile, electrostatic perturbations enhance the interaction energy between dislocations and surrounding ions. The superposition of these two effects means that dislocations must overcome a higher energy barrier to continue moving, ultimately manifesting as an improvement in the material's strength and hardness, thus achieving solid-solution strengthening. Additionally, the presence of impurity phases (CrNbO

4 and CrO

2 particles) in the CrTa

0.5Nb

0.5O

4 matrix exerts a dispersion strengthening effect. Dispersion strengthening enhances the material's resistance to deformation by means of second-phase particles such as fine impurity particles that impede dislocation motion. When the material undergoes plastic deformation under external force, dislocations need to traverse the impurity particles (i.e., CrNbO

4 and CrO

2 ) in the matrix. As dislocations propagate within the material, upon encountering CrNbO

4 and CrO

2 particles, they bend and loop around these particles to pass through. This process requires overcoming the line tension of the bent dislocations and consuming additional energy, which hinders the motion of dislocations. Consequently, the mechanical properties of the material, such as strength and hardness, are improved. The two mechanisms of solid-solution strengthening and dispersion strengthening can achieve the effects of "resistance superposition" and "spatial complementarity": the lattice distortion from solid-solution strengthening keeps dislocations in a state of continuous hindrance during long-distance movement, while the particle pinning from dispersion strengthening forms locally insurmountable obstacles. After dislocations break through the obstruction of the solid-solution stress field, they will soon encounter further interception by impurity particles. Meanwhile, significant lattice distortions were observed in CrO

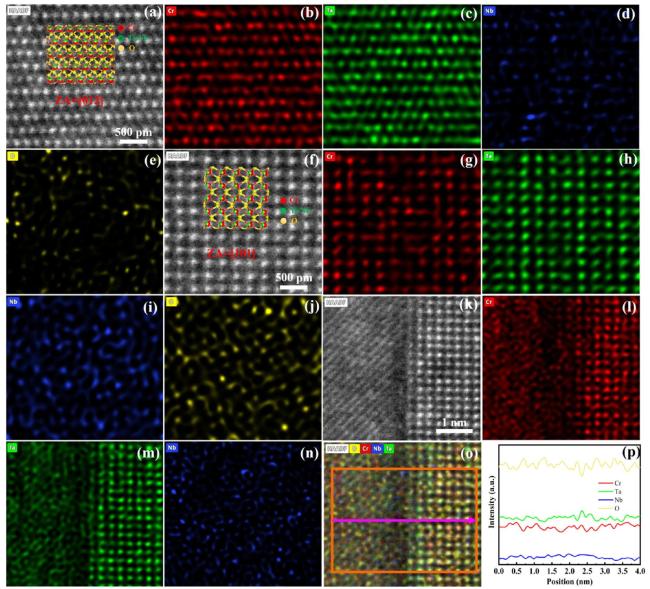

2 in

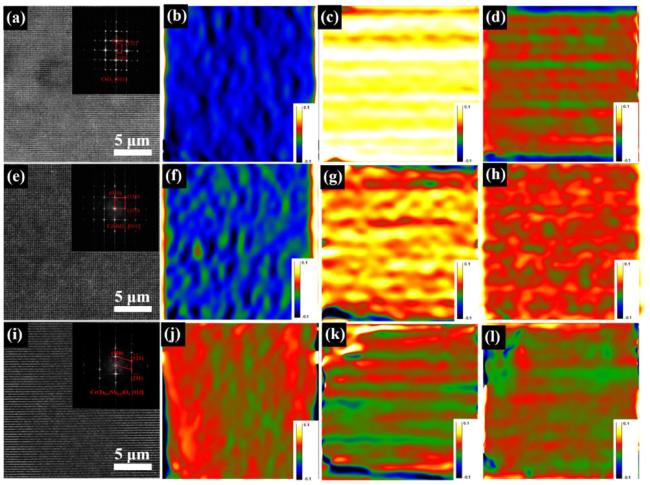

Figs. 7(e) and

Figs. 7(f), such as the areas marked by yellow circles. To characterize this phenomenon accurately, Geometric Phase Analysis (GPA) was employed for strain quantification, including quantitative studies on the distribution of CrO

2 along the [011] zone axis, as well as CrNbO

4 along the [001] zone axis and CrTa

0.5Nb

0.5O

4 along the [

113] zone axis. GPA analyses reveal that the mapping of horizontal normal strain (

εxx ), vertical normal strain (

εyy ) and shear strain (

εxy ) are randomly distributed. In the strain intensity color scale, white-blue pixels characterize regions of high strain, while red-green pixels correspond to states of low strain. The results in

Fig. 8 demonstrate that the strains in CrO

2 and CrNbO

4 are significantly greater than those in CrTa

0.5Nb

0.5O

4. This implies that within the material, CrTa

0.5Nb

0.5O

4 is subjected to a compressive stress, while CrO

2 and CrNbO

4 experience tensile stresses. Upon the application of external stress, the compressive stress in the CrTa

0.5Nb

0.5O

4 matrix counteracts part of the load, thereby enhancing the material's hardness, strength and toughness.