1. Introduction

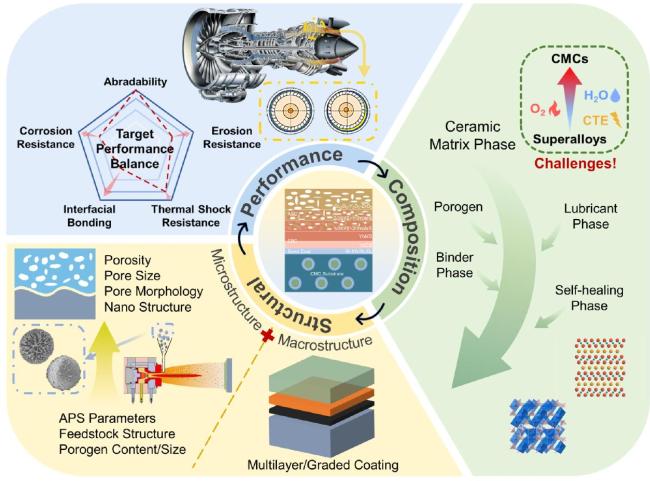

Fig. 2. A review of composition and structural design strategies for ceramic-based ASCs. |

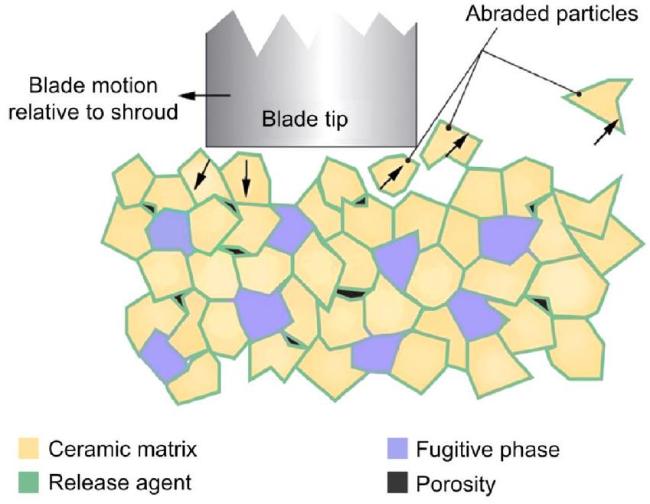

2. Basic composition and preparation methods of ceramic matrix high-temperature abradable sealing coatings

2.1. Basic composition

2.2. Preparation technology

2.3. Material systems

2.3.1. High-temperature abradable sealing coatings with superalloy substrates

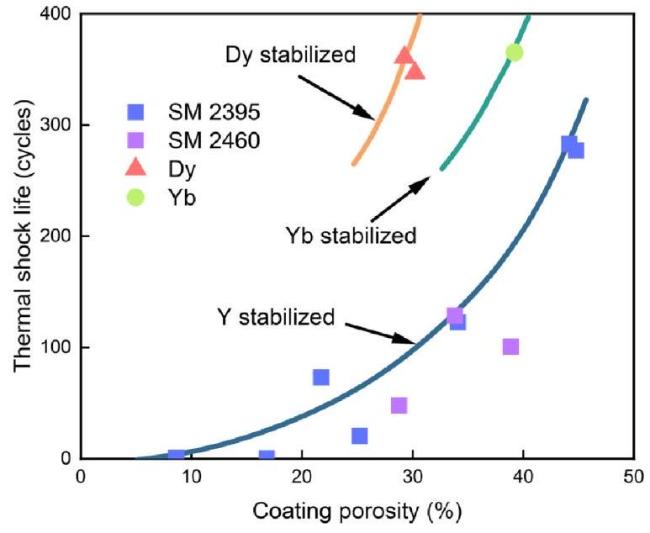

Fig. 3. Thermal shock life of ceramic ASCs as a function of their porosity[10]. |

Table 1 Regulation of coating porosity and microhardness [37]. |

| Feedstock | Power(kW) | Stand-off Distance (mm) | Porosity (Heat-treated) (% area) | Microhardness (Heat-treated) (HV0.1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBC | YbDS | 24 | 150 | 5.6±0.4 | 783.1±28.1 |

| ASC1 | YbDS | 12 | 125 | 8.8±0.8 | 695.6±42.3 |

| ASC2 | YbDS + 1.5wt% PE | 12 | 125 | 14.4+0.9 | 633.5+27.6 |

| ASC3 | YbDS + 4.5wt% PE | 12 | 125 | 18.9±2.1 | 553.9 + 50.0 |

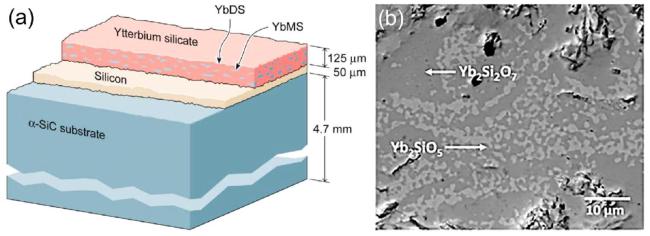

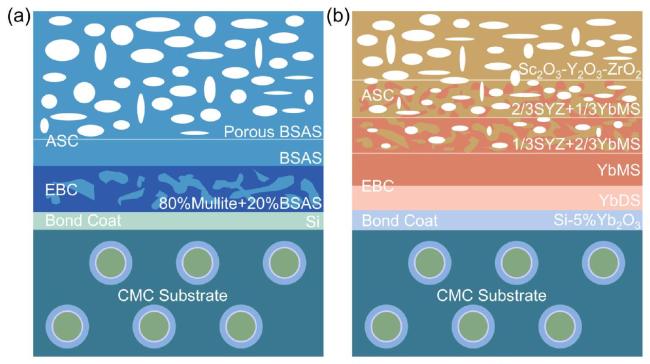

2.3.2. High-temperature abradable sealing coatings with CMC substrates

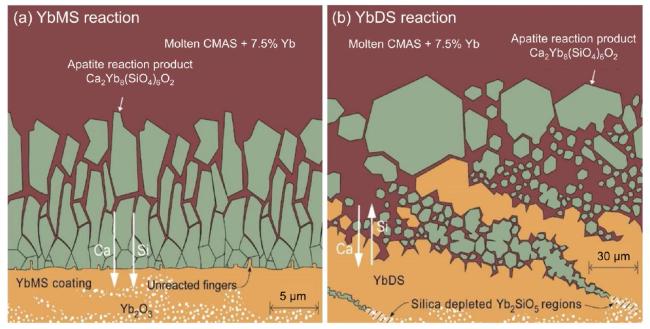

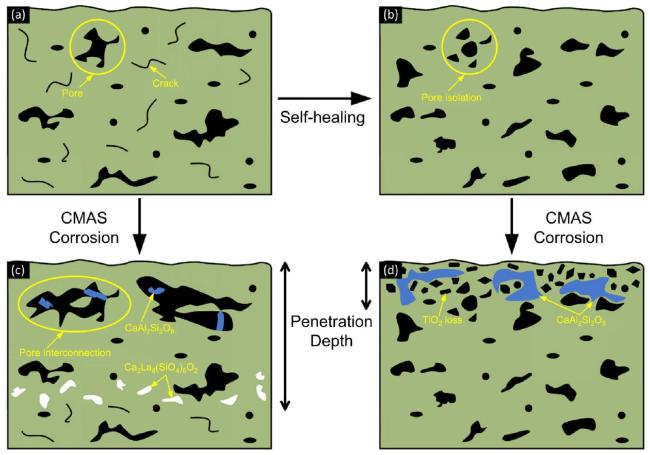

Fig. 5. CMAS corrosion failure mechanism of EBCs [47]. |

Table 2 Comparison of key performance indicators of coating materials for ASCs. |

| Material | Service temperature ( ∘C) | CTE (×10-6 K-1) | Thermal stability | Key advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YSZ | < 1200 | ∼10.7 (matches superalloy) | Good | Mature system, tunable porosity, good oxidation resistance | Upper temp limit ∼1200∘C, poor CMAS resistance |

| DySZ | ~1200 | Similar to YSZ | Better than YSZ | Improved phase stability, thermal shock resistance | Higher hardness, more blade wear |

| YbSZ | ~1200 | Similar to YSZ | Better than YSZ | Good thermal stability | Limited service temperature range |

| InFeO3(ZnO)m | < 1400 | ∼11.5 | Stable up to 1400∘C | Low hardness, good abradability | Poor erosion resistance |

| LMA | < 1600 | - | Excellent | High fracture toughness, low thermal conductivity | Uneven porosity, cracking under shock |

| YAG | < 1600 | - | Excellent | Good CMAS resistance, tunable porosity (SPPS) | - |

| BSAS | < 1300 | 4-6(matches CMCs) | Good | Good abradability, low silica activity | Glass phase formation at high temperature |

| YbMS | < 1500 | 7.5 | Excellent | Good thermal stability | CTE mismatch, interface spallation |

| YbDS | < 1400 | 4.5 | Good | Good CTE match, abradability | Poor water vapor/oxygen corrosion resistance |

3. Design strategies for coating composition and structure

Table 3 Contradictions among key performance indicators of coatings. |

| Performance Indicator | Functional Role | Enhancement Strategy | Negative Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abradability | Maintains blade-clearance control and avoids blade damage | Reduce hardness and increase porosity | May decrease bonding strength and erosion resistance |

| Erosion Resistance | Withstands high-speed particle impact | Increase surface hardness | May lead to increased blade wear and reduced abradability |

| Thermal Shock Resistance | Resists rapid temperature fluctuations, extends service life | Increase porosity and/or introduce nanostructures | May reduce mechanical strength |

| Corrosion Resistance | Resists water vapor and CMAS (calcium-magnesium-alumino-silicate) corrosion | Employ corrosion-resistant ceramic phases | Often associated with higher hardness or thermal stress |

| Bonding Strength | Enhances the durability of multilayer structures and prevents delamination | Surface texturing or bonding phase design | Risk of bonding phase oxidation or thermal stress accumulation |

3.1. Pore structure regulation

3.1.1. Addition and modification of pore-forming agents

3.1.2. Spray parameter optimization

Table 4 Influence of manufacturing process parameters on coatings microstructure and properties[20]. |

| Influence relative to the reference spraying parameters set of spraying parameters on coatings' structural attributes and properties | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium | Low | |

| Void content | |||

| Increase | None | None | |

| Decrease | | I+,Ar- | |

| Void size | |||

| Increase | | I- | |

| Decrease | | I+ | |

| Wear erosion resistance | |||

| Increase | I+ | | H2 +,Ar-,Ar+ |

| Decrease | I- | | |

| Calculated Young modulus | |||

| Increase | | I-,Ar+ | I+,H2 +,H2 -,Ar- |

| Decrease | None | | |

| Calculated thermal conductivity | |||

| Increase | | I+,Ar+ | H2 +,H2 -,Ar- |

| Decrease | | I- | |

*I: Arc current intensity; Ar: Argon plasma forming gas flow rate; H: Hydrogen plasma forming gas fraction; Dspray : Spraying distance; dpowder: powder feed rate. ** + :Increase; -: Decrease. |

3.1.3. Feedstock powder structure design

3.2. Nanostructured composite design

Table 5 Comparison of fabrication methods for nanocomposite coatings. |

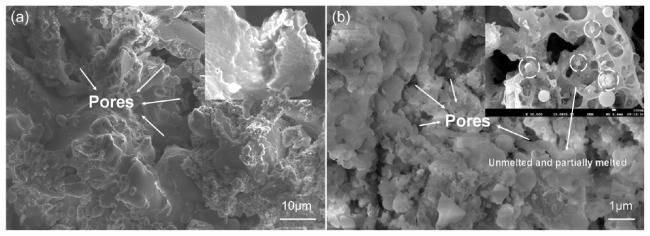

Fig. 7. SEM images of (a) APS coating (C-YSZ) and (b) SPPS coating (M-YSZ) [64]. |

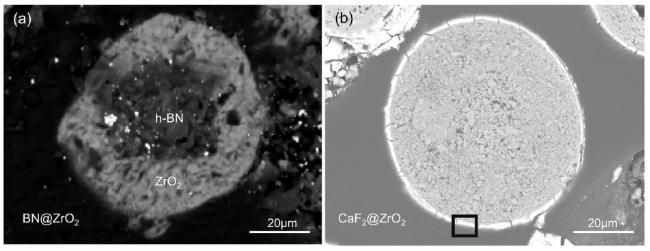

3.3. Incorporation and modification of lubricating phases

Table 6 Comparison of lubricating phase materials for high-temperature coatings. |

| Lubricating phase | High-Temperature stability | Friction coefficient | Abradability enhancement | Oxidation stability | Drawbacks | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h-BN | Moderate | Low | Significant improvement | Poor | Easily forms oxides above 900∘C | [23,38,71,72] |

| CaF2 | High | Low | Good | Good | Melts at high temperatures; prone to infiltration | [73-75] |

| Ti3AlC2 | High | Moderate | Good | Good | Partial decomposition during spraying | [76-78] |

| LaPO4 | High | Moderate | Moderate | Good | Limited compatibility with YSZ | [79] |

3.4. Binder phases and self-healing mechanisms

Table 7 The functions of different binding phases[80]. |

| Deposition efficiency | Thermal cycles | Fracture toughness | Failure mechanism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 10.37 % | 67.3 | 1.66MPa⋅m1/2 | Brittle fracture |

| Al2O3 | 18.23 % | - | - | - |

| MgAl2O4 | 29.19 % | 96.7 | 2.32MPa⋅m1/2 | Ductile fracture |

| YAG | 16.51 % | - | - | - |

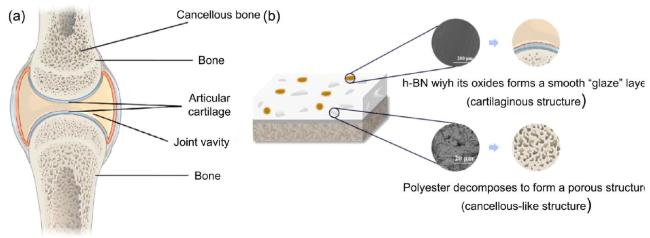

Fig. 9. The diagram of (a) knee articulation and (b) YSZ-based ASC with an articulation mimicking structure [84]. |

Fig. 10. Schematic diagram of the self-healing mechanism of porous LMA-based ASCs and CMAS corrosion behavior [88]. |

3.5. Multilayer structural design

Fig. 12. Schematic illustration of the single-layer 75YbDS-25YbMS, 25YbDS-75YbMS, and gradient EBC after water vapor corrosion [102]. |

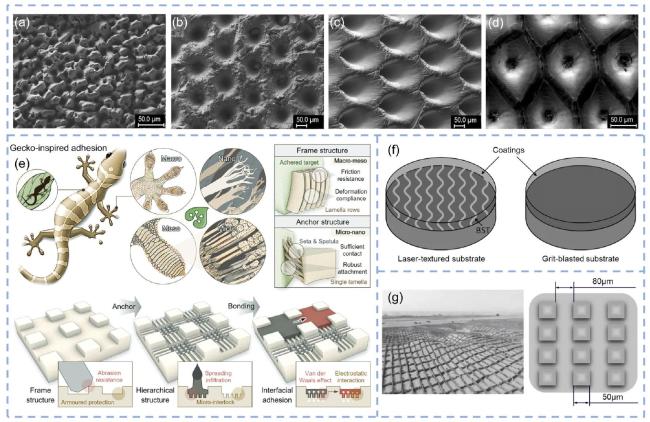

3.6. Surface texturing treatment

Fig. 13. Surface micro-textures for enhanced coating adhesion: SEM and schematic representations. (a) Random micro-texture pattern;(b) Regular circular pore array;(c) Inclined hole texture;(d) Hexagonal texture array;(e) Schematic of multi-scale hierarchical bioinspired structure;(f) Comparative schematic of bioinspired micro-texture versus grit-blasted substrate with top coating;(g) Square-grid micro-texture schematic. [116,115,118]. |

4. Evaluation Methods

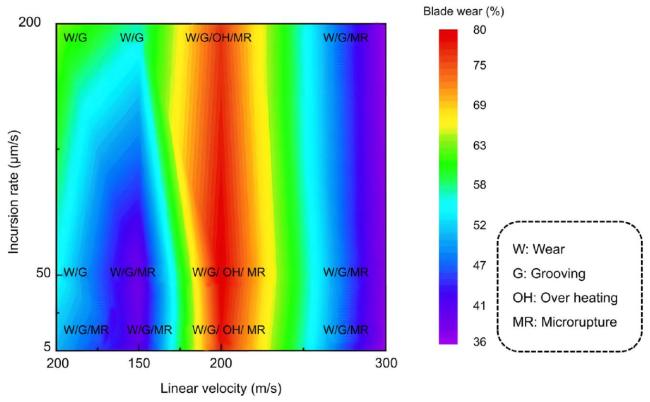

4.1. Tribological performance

4.1.1. Fundamentals of tribology

Fig. 14. Typical wear map of ceramic-based ASCs [128]. |

Fig. 15. Wear mechanism model of ceramic-based ASCs [130]. |

4.1.2. Abradability

Table 9 Domestic evaluation methods for the abradability of seal coatings. |

| Method | Principle Description | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scratch Method | Measures mass loss caused by a stylus scratching the coating under a constant load; greater mass loss indicates better abradability. | Simple and easy to implement | Significant deviation from actual service conditions |

| Scratch Hardness Method | Uses an indenter of defined shape to create scratches on the coating surface; abradability is characterized by scratch hardness related to scratch width. | Simple and easy to implement | Significant deviation from actual service conditions |

| Turning Method | A blade is used to machine a rod coated with the sealing layer at a cutting depth of 0.6 mm ; the time required to cut this depth is used to evaluate abradability. | Simple and easy to implement | Lacks heating and temperature control devices |

| Impact Wear Method | Uses an impact wear tester to measure the wear energy of the coating; lower wear energy indicates better abradability. | Introduces a quantitative evaluation standard | Far from actual service conditions; suitable only for theoretical research |

| Sliding Wear Method | Employs a ring-on-block wear tester to measure the wear rate between a metallic block and a coated block under specific conditions. | Closely simulates service conditions | Low linear velocity; still deviates from actual conditions |

| Disc Milling Method | The sealing coating is applied to the end surface of a pin, which is then tested against a rotating disc; abradability is characterized by the measured wear rate. | Higher linear velocity ( | Lacks heating and temperature control; deviates from actual conditions |

| Bench Test Method | Simulates real engine operation; abradability is evaluated based on coating performance and blade condition. | Closely simulates service environment | High cost; lacks standardized evaluation criteria |

Fig. 16. Schematic diagram of the abradability test rig[134]. |

Table 10 The abradability performance of several typical ceramic-based ASCs. |

| Coating system | Coefficient of friction (COF) | Specific wear rate (cm3/(N⋅m)) | Incursion depth ratio (IDR) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni-YSZ | 0.22(700∘C) | - | - | [136] |

| YSZ/ BN@ZrO 2 | 0.5 (RT) | 6.58±0.24×10-4 | 13 % (RT) | [71] |

| 0.3(1000∘C) | 64%(1000∘C) | |||

| YSZ/BN-polyester | 0.42 (RT) | 1.01±0.25×10-3 | 8 % (RT) | [84] |

| 0.22(1000∘C) | 66%(1000∘C) | |||

| | 0.65 (RT) | 6.5×10-3 | - | [101] |

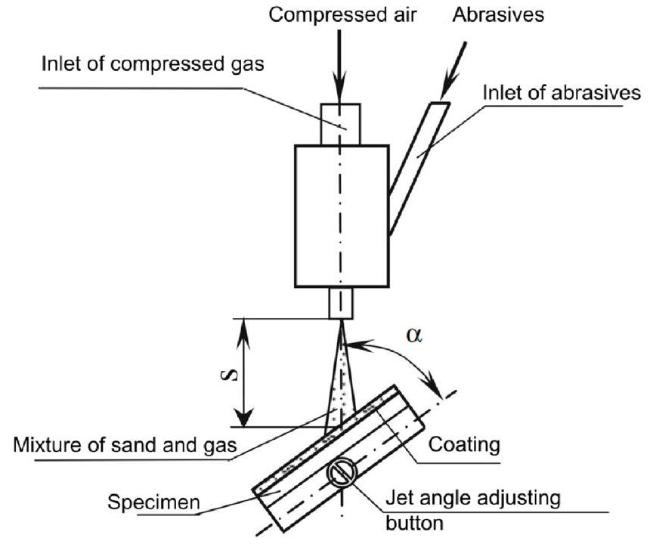

4.1.3. Erosion resistance

Fig. 17. Schematic diagram of the erosion test apparatus [139]. |

4.2. Mechanical properties

4.2.1. Surface rockwell hardness

4.2.2. Bond strength

4.3. Thermal shock resistance

4.4. Corrosion resistance

4.4.1. CMAS corrosion

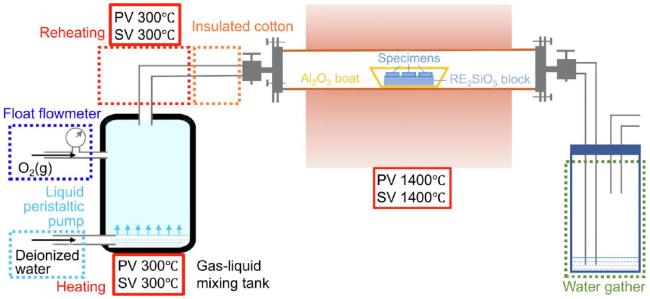

4.4.2. Water vapor corrosion

Fig. 18. Schematic diagram of the water vapor corrosion testing apparatus [149]. |