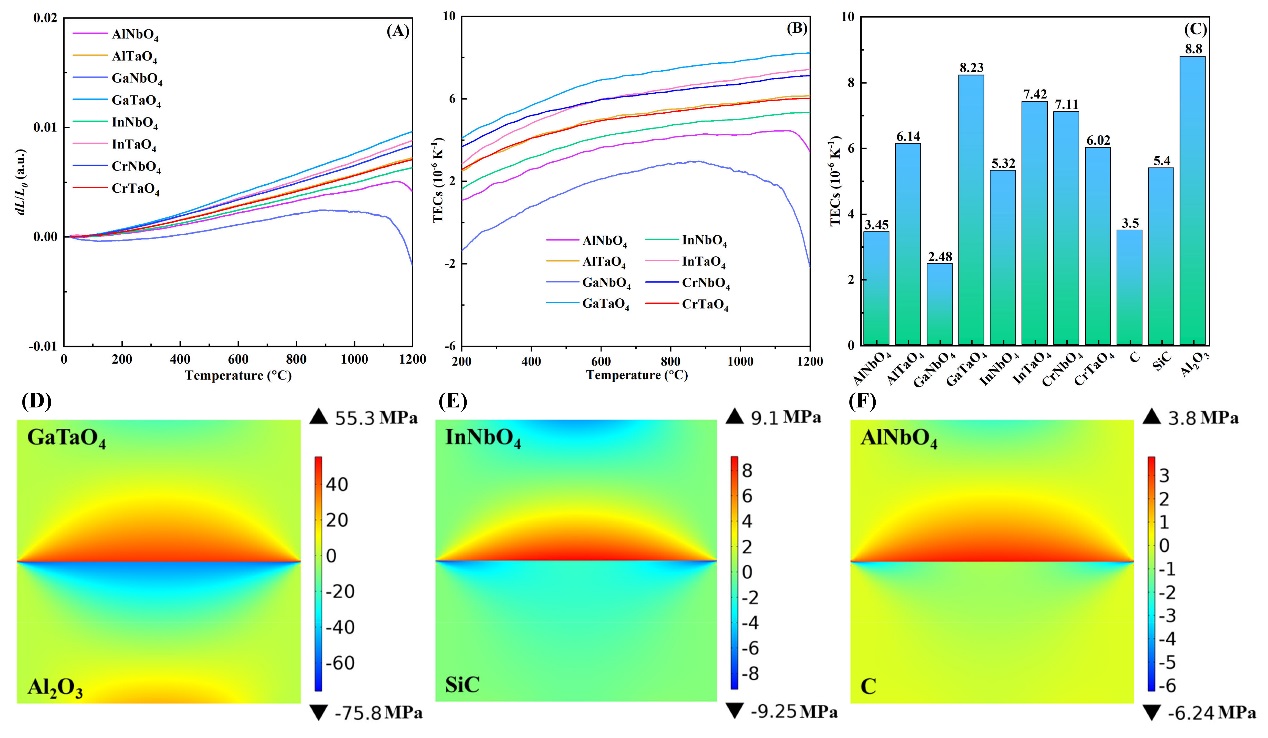

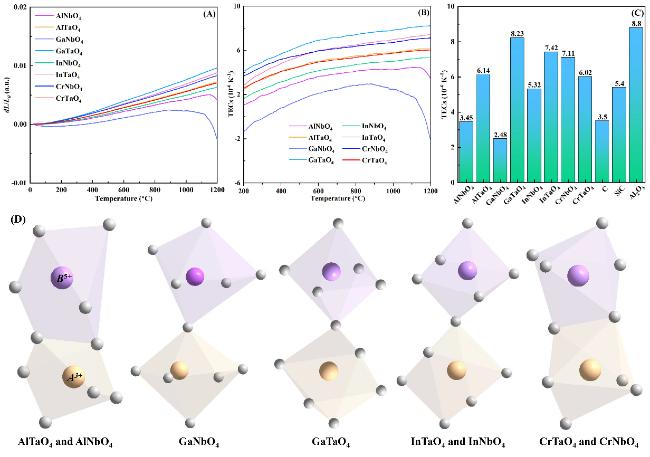

Fig. 4(A) shows the thermal expansion rate of each sample, including AlNbO

4 and AlTaO

4, which increases with the increasing temperature, except GaNbO

4 and AlNbO

4. An obvious reduction in thermal expansion rate is found in AlNbO

4 and GaNbO

4 at temperatures higher than 1150 and 1100 ºC, respectively, which is caused by their relatively low melting points. AlNbO

4 and GaNbO

4 have a melting point of 1540 ºC and 1420 ºC [

37,

38], respectively, and other

ABO

4-type oxides have higher melting points. The changes of TECs of

ABO

4-type oxides are shown in

Fig. 4(B). The TECs of GaNbO

4 decrease slightly at 900~1100 °C, while they decrease dramatically at 1100~1200 °C. GaNbO

4 has the lowest melting point among the studied oxides, and high temperatures will soften GaNbO

4 to reduce its TECs. GaTaO

4 has the highest TECs (8.23×10

-6 K

-1, 1200 ºC) among the studied oxides, which approaches those of Al

2O

3 CMCs (8.80×10

-6 K

-1), and its TECs increase with the increasing temperature. Except AlNbO

4 and GaNbO

4, the TECs of other

ABO

4-type oxides are 5.32~8.23×10

-6 K

-1 at 1200 ºC, which are suitable for EBC applications for different CMCs. C-, SiC-, and Al

2O

3-based CMCs have TECs of approximately 3.5×10

-6 K

-1, 5.4×10

-6 K

-1, and 8.8×10

-6 K

-1 at 1200 ºC, respectively as shown in

Fig. 4(C) [

39⇓-

41]. The thermal stress between oxide EBCs and substrates is dominated by TECs, and it is obvious that AlNbO

4, InNbO

4, and GaTaO

4 are potential EBCs for C-, SiC-, and Al

2O

3-based CMCs, respectively.