M

n+1AX

n phase (

n=1-3 ) is a kind of ternary layered compound first proposed by Nowotny et al., where M is the early transition metal element, A is the main group element, X is carbon, nitrogen, and boron which was recently found to be the X element [

13]. Barsoum et al. synthesized dense MAX phase of Ti

3SiC

2 by hot pressing and reported a series of unique properties of this kind of compound, including high conductivity, high flexural strength, high fracture toughness, excellent processability, and so on [

14,

15]. These excellent properties have attracted considerable attentions from MAX phases for decades [

16-

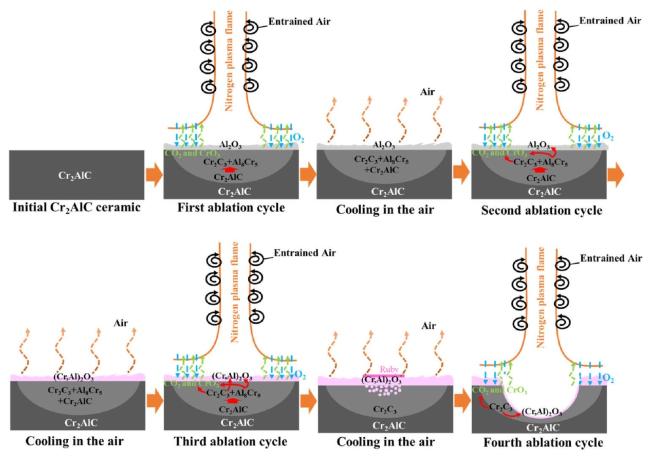

22]. In previous studies, it has been found that MAX phase ceramics form an oxide protective layer of A element on the surface when exposed to high-temperature oxidation environments, thereby protecting the integrity of the internal structure. Song et al. studied the oxyacetylene flame ablation properties of Ti

2AlC MAX phase ceramics above 1800

∘C and obtained linear and mass ablation rates as low as 0.08μ m/s and -180μ g/s in 180 s. It was found that Ti

2AC would be oxidized to TiO

2,Al

2O

3, and CO

2 during the ablation process, with TiO

2 and Al

2O

3 further combining to form Al

2TiO

5, which will provide protection during the ablation process [

23]. Su et al. also found a similar phenomenon in the study of the ablation mechanism of Ti

3SiC

2 MAX phase ceramics. Ti

3SiC

2 ceramics maintained structural stability after being ablated by a 1600

∘C nitrogen plasma flame for 120 s, and an oxide protective layer of TiO

2 and SiO

2 was formed on its surface. After 120 s of ablation, the linear ablation rate of Ti

3SiC

2 ceramic is the is 5.58μ m/s and the mass ablation rate is -0.23μ g/s [

24]. Hu et al. studied the ablation performance of Cr

2AlC at ultrahigh temperatures using an oxyacetylene torch and discussed its mechanism. In their research, a large amount of unoxidized carbides were found on the surface, which may be related to the reducing flame they used. At ultra-high temperatures, Cr

2AlC still exhibits a linear ablation rate of 44.2μ m/s and a mass ablation rate of 13mg/s [

25]. In summary, MAX phase ceramics exhibit excellent ablation performance due to the formation of oxide protective layer, making them a potential A-TPS material.