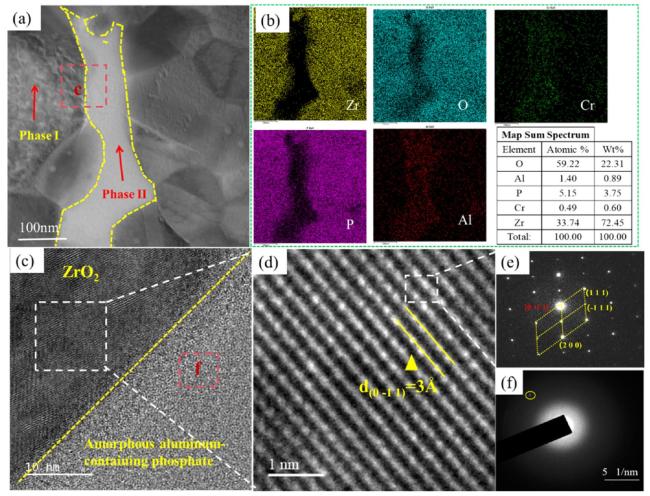

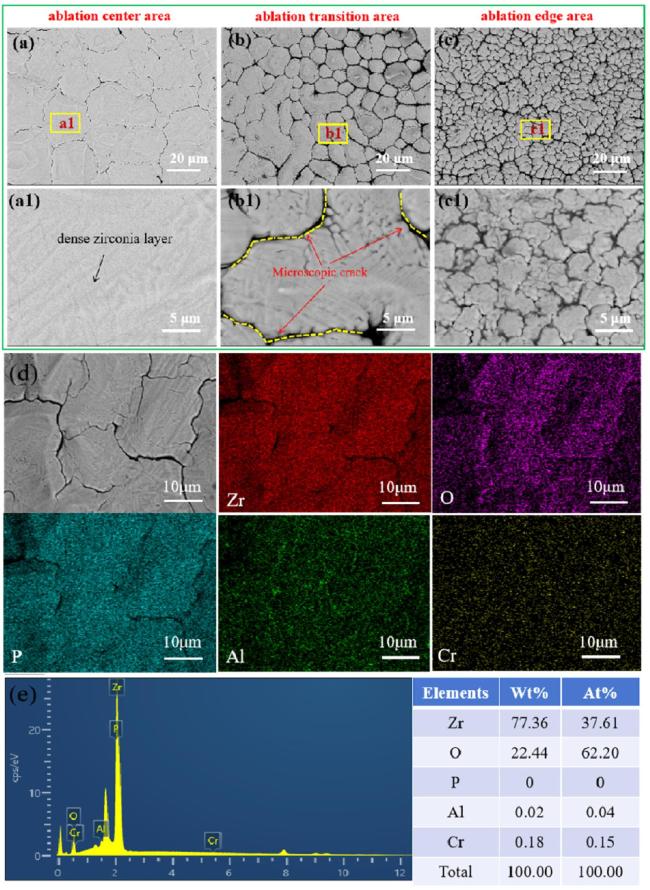

To further analyze the microstructure of the zirconium-based phosphate material, this study utilized transmission electron microscopy to analyze the phase distribution.

Fig. 3(a) shows a high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) image of the zirconium-based phosphate material, which shows that the phases are closely combined, and no defects such as cracks and pores appear. Subsequently, EDS mapping was used to analyze the material, as shown in

Fig. 3(b). Clearly, the material is divided into two phases. Phase I is primarily composed of zirconia phase and phosphorus phase enriched on its surface, while Phase II is dominated by aluminum phosphate phase. Comparative analysis revealed a distinct selective enrichment of phosphorus in Phase I. The formation mechanism of this phenomenon can be attributed to the following synergistic processes[

1-

3]: first, Al

3+ and Cr

3+ preferentially coordinate with phosphate ions in the solution to form an amorphous AlPO

4-CrPO

4 network structure; second, due to the significant interfacial energy difference between this amorphous network and the zirconia surface, free phosphate ions (PO

4 3-) that did not participate in coordination are expelled during the condensationcrystallisation process; Subsequently, these negatively charged phosphate ions are captured by the abundant Zr-OH

2 +/Zr-OH groups on the zirconia surface through electrostatic interactions; Finally, during the dehydration-condensation process, the phosphate ions form stable compounds with the zirconia surface through the formation of

Zr-O-P covalent bonds or the generation of zirconium pyrophosphate (ZrP

2O

7, confirmed by XRD in

Fig. 2b), thereby creating a characteristic phosphorus enrichment layer on the surface of the zirconia particles. Moreover, it is found that the atomic percentages of oxygen and zirconium were found to be relatively high, reaching 59.22% and 33.74% respectively. The selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) of the zirconium-based phosphate material provides a deeper understanding of the crystal structure of the composite phase.

Fig. 3(c) clearly confirms that the two phases are closely combined and that no obvious intermediate phase has formed. The electron diffraction pattern of ZrO

2 was analyzed, and the interplanar spacing was measured to be 3Å (

Fig. 3(d)), corresponding to the (111) plane. The interplanar spacing of the (-211) plane measured in another direction was 2.78Å. Therefore, this ZrO

2 mainly had a cubic phase structure. The corresponding aluminum-containing phosphate phase was mainly amorphous. No lattice fringes appear in this image, and only a small number of diffraction spots exist in the electron diffraction pattern (

Fig. 3(f)).