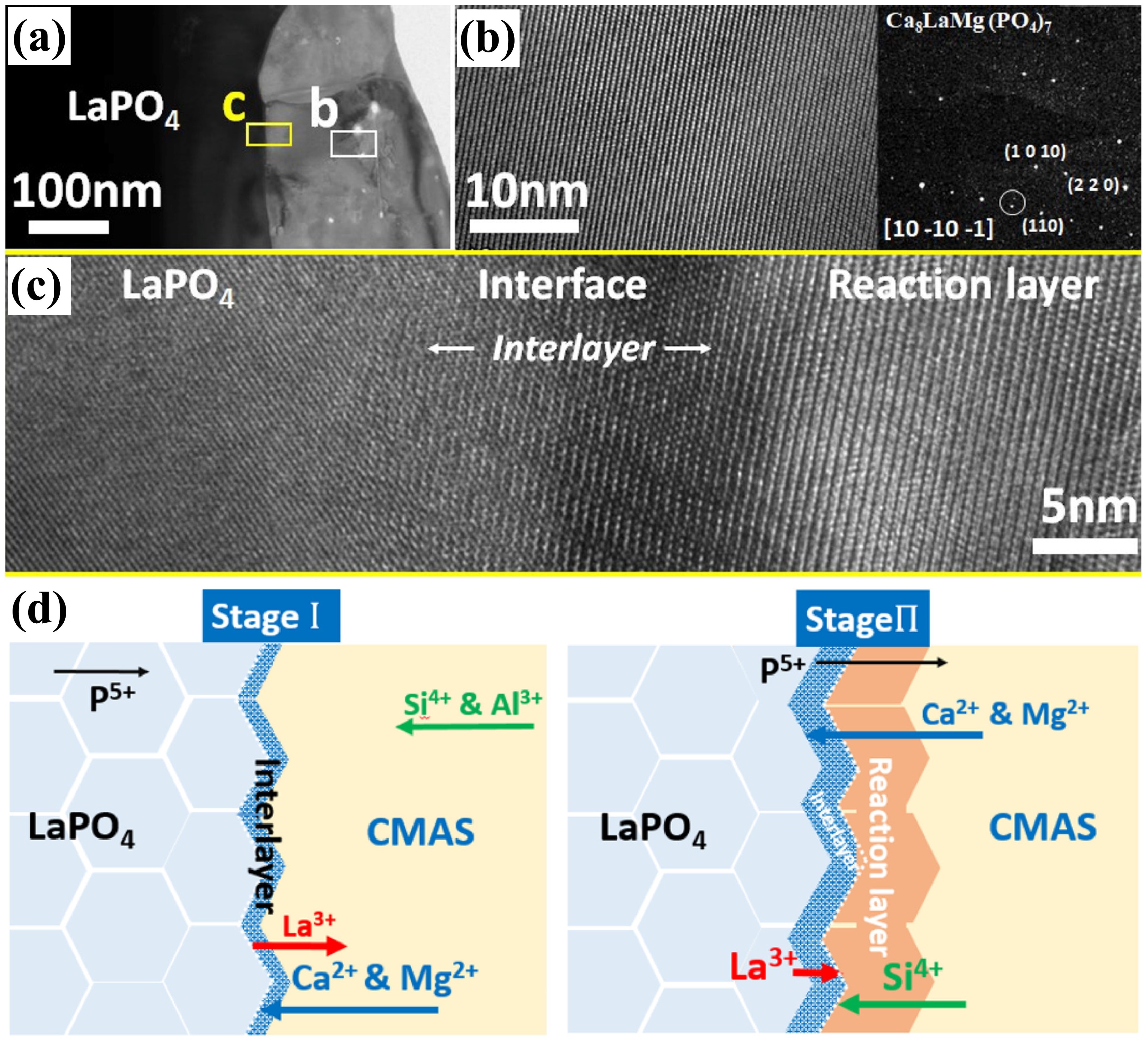

Fig. 3 (a) C-17 military aircraft ingesting sand during take-off on unimproved runway Inset: Gas turbine engine vanes with molten CMAS deposits, (b) NAVY V-22 rotorcraft performing landing maneuver under severe ‘brown-out’ heavy dust/sand conditions, (c) Dust storm across the Red Sea May 13, 2005, (d) A plane passing through a cloud of volcanic ash, and (e) Volcanic ash deposited on aircraft. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

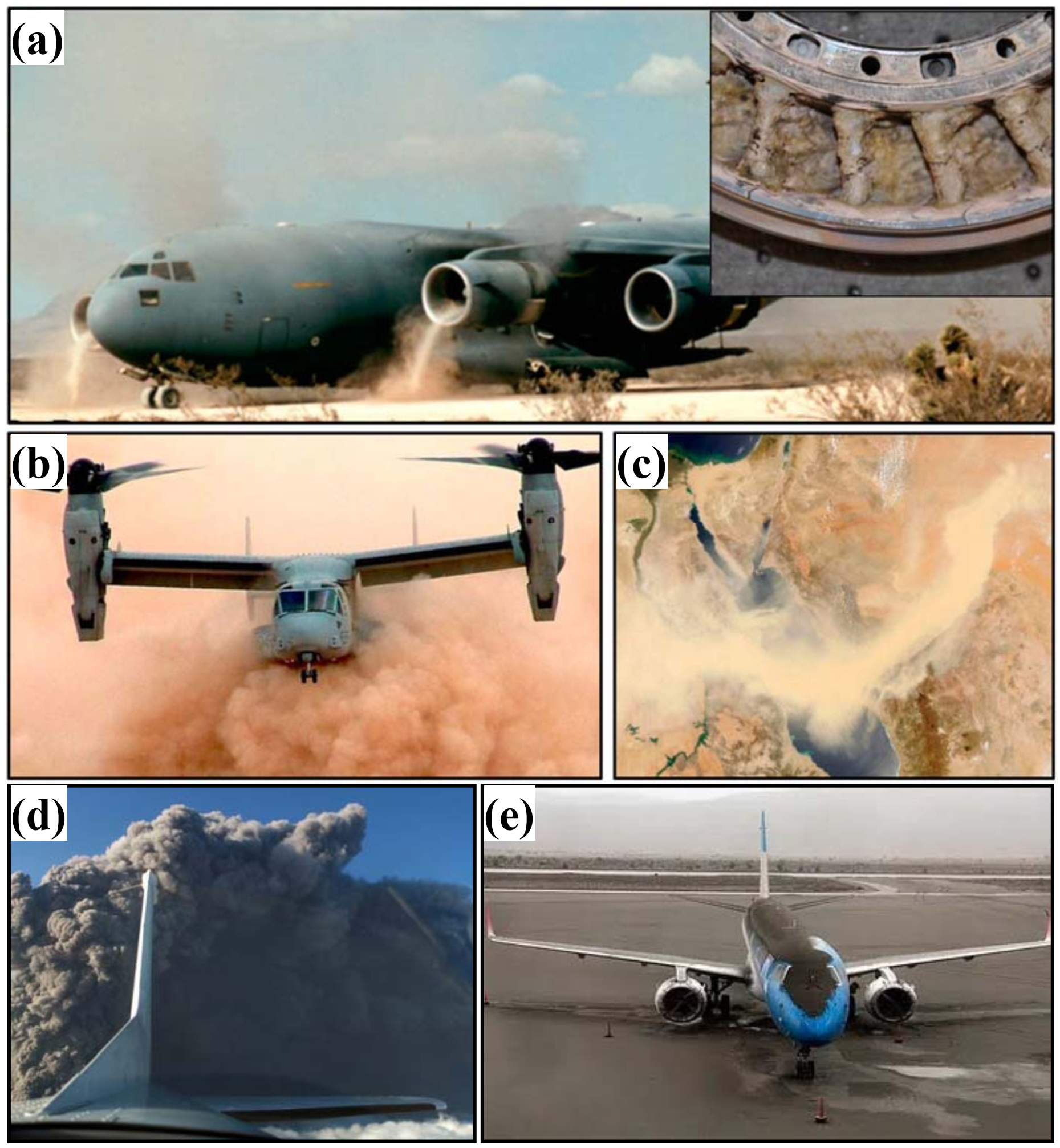

Fig. 3 (a) C-17 military aircraft ingesting sand during take-off on unimproved runway Inset: Gas turbine engine vanes with molten CMAS deposits, (b) NAVY V-22 rotorcraft performing landing maneuver under severe ‘brown-out’ heavy dust/sand conditions, (c) Dust storm across the Red Sea May 13, 2005, (d) A plane passing through a cloud of volcanic ash, and (e) Volcanic ash deposited on aircraft. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [ Fig. 10 (a) Schematic diagram of the volcanic ash melting process; (b) Transition temperatures of volcanic ash with different compositions at various stages; (c) Photographs of volcanic ash at different melting stages; (d) Backscattered electron images of volcanic ash at various melting stages. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

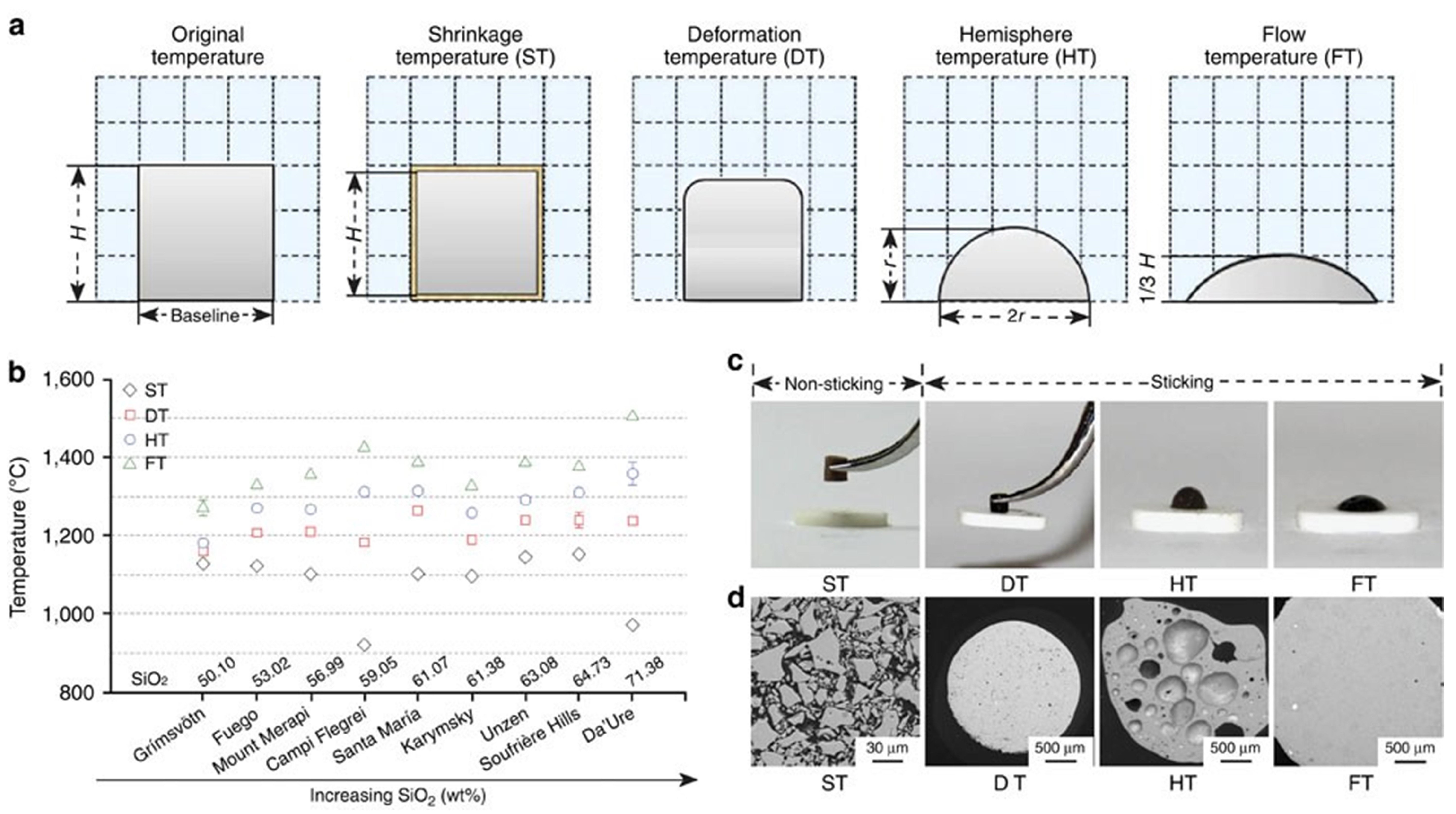

Fig. 10 (a) Schematic diagram of the volcanic ash melting process; (b) Transition temperatures of volcanic ash with different compositions at various stages; (c) Photographs of volcanic ash at different melting stages; (d) Backscattered electron images of volcanic ash at various melting stages. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [ Fig 16. (a) Bright-field TEM image of CMAS infiltration front at 1250 ℃ for 2 h in 8YSZ TBC, (b-c) HAADF image, and the corresponding Ca mapping of the dashed rectangle area in (a). The table at the bottom right lists the chemical compositions of points A, B, and C in (b). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

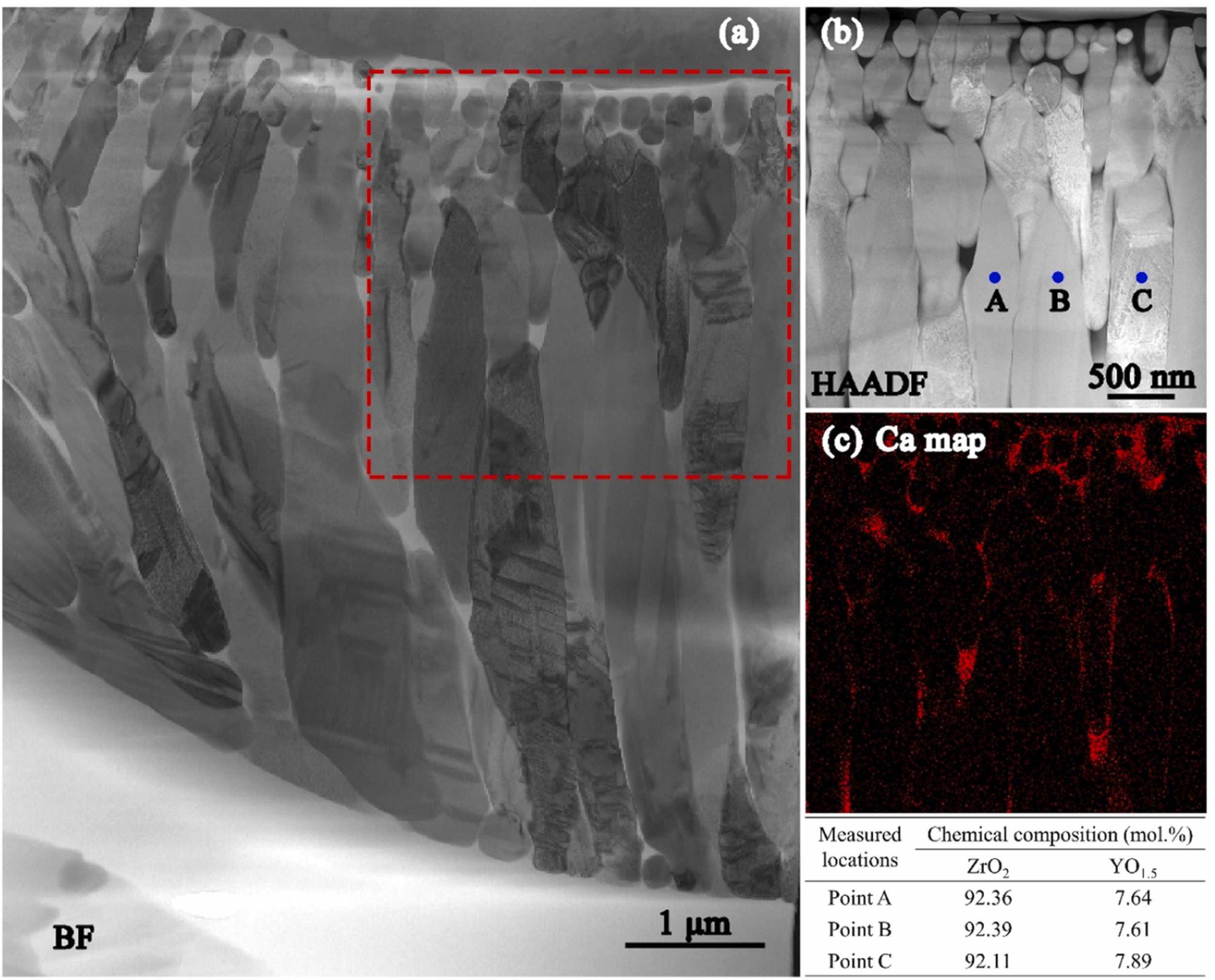

Fig 16. (a) Bright-field TEM image of CMAS infiltration front at 1250 ℃ for 2 h in 8YSZ TBC, (b-c) HAADF image, and the corresponding Ca mapping of the dashed rectangle area in (a). The table at the bottom right lists the chemical compositions of points A, B, and C in (b). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [ Fig. 17. (a) SEM and EDS images of the interaction layer on cross-section, (b) the thickness of the reaction layer at different holding times, and (c-d) cross-section of the CMAS/YSZ interaction zone in the dissolution/reprecipitation process. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

Fig. 17. (a) SEM and EDS images of the interaction layer on cross-section, (b) the thickness of the reaction layer at different holding times, and (c-d) cross-section of the CMAS/YSZ interaction zone in the dissolution/reprecipitation process. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [ Fig. 18. Typical microstructure and the microstructure after CMAS of TBC prepared by APS and EB-PVD: (a) 7YSZ TBC prepared by APS and (b) EB-PVD, (c) microstructures of 8YSZ APS TBC after CMAS corrosion at 1250 ℃ for 3 h and (d) microstructures of 7YSZ EB-PVD TBC after CMAS corrosion at 1300 ℃ for 4 h. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

Fig. 18. Typical microstructure and the microstructure after CMAS of TBC prepared by APS and EB-PVD: (a) 7YSZ TBC prepared by APS and (b) EB-PVD, (c) microstructures of 8YSZ APS TBC after CMAS corrosion at 1250 ℃ for 3 h and (d) microstructures of 7YSZ EB-PVD TBC after CMAS corrosion at 1300 ℃ for 4 h. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [ Fig. 19. (a) Schematic representation of the envisaged mechanism leading to the microstructure of the RE2Zr2O7 reaction layer, (b) bright field TEM micrograph of the corrosion reaction zone of the RE2Zr2O7. Phases: z’: fluorite, a: apatite, s: spinel, p: pore, c’: CMAS, (c) Back-scattering SEM images demonstrating the crystallization products in different RE2Zr2O7-CMAS systems from high-temperature reaction experiments conducted at 1300 ℃/30 min. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

Fig. 19. (a) Schematic representation of the envisaged mechanism leading to the microstructure of the RE2Zr2O7 reaction layer, (b) bright field TEM micrograph of the corrosion reaction zone of the RE2Zr2O7. Phases: z’: fluorite, a: apatite, s: spinel, p: pore, c’: CMAS, (c) Back-scattering SEM images demonstrating the crystallization products in different RE2Zr2O7-CMAS systems from high-temperature reaction experiments conducted at 1300 ℃/30 min. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [ Fig. 22. The interface microstructure, wetting process on-line photographs and atomic arrangement of GdTaO4 and YbTaO4: (a) the interface microstructure of GdTaO4 and CMAS (33Ca-9Mg-13Al-45Si) at 1350 ℃ for different time, (b) the surface state of GdTaO4 and YSZ before and after high-temperature reaction, (c) the atomic arrangement of CaMgSi2O6, Ca2Ta2O7, GdTaO4 and YbTaO4 and (d) images of the reaction interface between residual CMAS and substrate. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

Fig. 22. The interface microstructure, wetting process on-line photographs and atomic arrangement of GdTaO4 and YbTaO4: (a) the interface microstructure of GdTaO4 and CMAS (33Ca-9Mg-13Al-45Si) at 1350 ℃ for different time, (b) the surface state of GdTaO4 and YSZ before and after high-temperature reaction, (c) the atomic arrangement of CaMgSi2O6, Ca2Ta2O7, GdTaO4 and YbTaO4 and (d) images of the reaction interface between residual CMAS and substrate. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [ Fig. 23. Corrosion mechanism of M-YTaO4: (a) images of cross-sections and grain boundary infiltration depths of M-YTaO4 after CMAS corrosion, (b) schematic diagram of CMAS corrosion of M-YTaO4, (c) the interface between residual CMAS melt and M-YTaO4 substrate after CMAS corrosion at 1300 ℃ for 5 h, (d) Mapping and (e) section lines of reduced moduli corresponding to (c). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

Fig. 23. Corrosion mechanism of M-YTaO4: (a) images of cross-sections and grain boundary infiltration depths of M-YTaO4 after CMAS corrosion, (b) schematic diagram of CMAS corrosion of M-YTaO4, (c) the interface between residual CMAS melt and M-YTaO4 substrate after CMAS corrosion at 1300 ℃ for 5 h, (d) Mapping and (e) section lines of reduced moduli corresponding to (c). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [ Fig. 24. (a-c) SEM images of the cross-sectional morphologies of LMA/GdPO4 after CMAS corrosion, (d) Schematic diagrams of CMAS wetting behavior of GdPO4 and Gd2Zr2O7, and cross-sectional images of contact angles of CMAS droplets on (e-e2) GdPO4, (f-f2) Gd2Zr2O7, and (g-g2) YSZ. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

Fig. 24. (a-c) SEM images of the cross-sectional morphologies of LMA/GdPO4 after CMAS corrosion, (d) Schematic diagrams of CMAS wetting behavior of GdPO4 and Gd2Zr2O7, and cross-sectional images of contact angles of CMAS droplets on (e-e2) GdPO4, (f-f2) Gd2Zr2O7, and (g-g2) YSZ. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [ Fig. 28 (a) The recession layer thickness of X1-RE2SiO5 (RE = La, Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd) after CMAS corrosion at 1300 ℃ for 25 h; (b) The recession layer thickness of X2- RE2SiO5 (RE = Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Y, Tm, Yb, and Lu) after CMAS corrosion at 1300 ℃for 50 h and 100 h; (c) Schematic diagram of CMAS corrosion of X2-RE2SiO5 at 1300 ℃. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

Fig. 28 (a) The recession layer thickness of X1-RE2SiO5 (RE = La, Nd, Sm, Eu, Gd) after CMAS corrosion at 1300 ℃ for 25 h; (b) The recession layer thickness of X2- RE2SiO5 (RE = Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Y, Tm, Yb, and Lu) after CMAS corrosion at 1300 ℃for 50 h and 100 h; (c) Schematic diagram of CMAS corrosion of X2-RE2SiO5 at 1300 ℃. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [ Fig. 36 (a-c) Cross-sectional morphology of γ-Y2Si2O7, β-Yb2Si2O7, and β-Sc2Si2O7 after CMAS corrosion at 1500 ℃; (d) Schematic diagram of the formation of “blister” cracks. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

Fig. 36 (a-c) Cross-sectional morphology of γ-Y2Si2O7, β-Yb2Si2O7, and β-Sc2Si2O7 after CMAS corrosion at 1500 ℃; (d) Schematic diagram of the formation of “blister” cracks. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [ Fig. 39 A cross-sectional SEM images of the Al2O3-YSZ coating exposed to (a-b) CMAS, (c-d) CMAS+NaVO3 powders, (e-f) CMAS+Na2SO4 powders, and (g-h) CMAS+NaCl powders for 10 h, and corresponding EDS mapping results (Ca, Mg, Al, and Si elements) are also provided. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

Fig. 39 A cross-sectional SEM images of the Al2O3-YSZ coating exposed to (a-b) CMAS, (c-d) CMAS+NaVO3 powders, (e-f) CMAS+Na2SO4 powders, and (g-h) CMAS+NaCl powders for 10 h, and corresponding EDS mapping results (Ca, Mg, Al, and Si elements) are also provided. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [ Fig. 40 (a) Superhydrophobic lotus leaf and its microstructure-the source of inspiration. (b) PS-PVD TBCs preparation. (c) Constructing the lotus leaf structure on PS-PVD TBCs surface. (d) Schematic diagram of femtosecond laser processing system and fabrication of micro-nanostructured PS-PVD TBCs. (e) Al film deposition by magnetron sputtering. (f) In situ synthesis of Al-modified layer on laser textured PS-PVD TBCs by vacuum heat treatment. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

Fig. 40 (a) Superhydrophobic lotus leaf and its microstructure-the source of inspiration. (b) PS-PVD TBCs preparation. (c) Constructing the lotus leaf structure on PS-PVD TBCs surface. (d) Schematic diagram of femtosecond laser processing system and fabrication of micro-nanostructured PS-PVD TBCs. (e) Al film deposition by magnetron sputtering. (f) In situ synthesis of Al-modified layer on laser textured PS-PVD TBCs by vacuum heat treatment. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [ Fig. 41 (a) Volcanic ash accumulation on turbine blades leading to engine failure. (b) Lotus leaf-inspired superhydrophobicity for CMAS-phobic surface design. (c) Micro/nano hierarchical structure on TBC surface reducing CMAS deposition. (d) Biomimetic structure application on turbine blades to prevent CMAS adherence. (e) Ultrafast laser direct writing for micro/nano hierarchical structure on (Gd0.9Yb0.1)2Zr2O7 material. (f) PS-PVD process for CMAS-phobic coating with microconical papillae and nanoparticles. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

Fig. 41 (a) Volcanic ash accumulation on turbine blades leading to engine failure. (b) Lotus leaf-inspired superhydrophobicity for CMAS-phobic surface design. (c) Micro/nano hierarchical structure on TBC surface reducing CMAS deposition. (d) Biomimetic structure application on turbine blades to prevent CMAS adherence. (e) Ultrafast laser direct writing for micro/nano hierarchical structure on (Gd0.9Yb0.1)2Zr2O7 material. (f) PS-PVD process for CMAS-phobic coating with microconical papillae and nanoparticles. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [ Fig. 43 (a) Collage of cross-sectional optical micrographs of β-Yb2Si2O7/1 vol% CMAS pellet that have interacted with CMAS at 1500 ℃ for 24 h. The region between the arrows is where the CMAS was applied. (b) Cross-sectional SEM image of the whole pellet from the region I. (c) Higher-magnification cross-sectional SEM image of the region II, and (d) corresponding EDS elemental Ca map. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

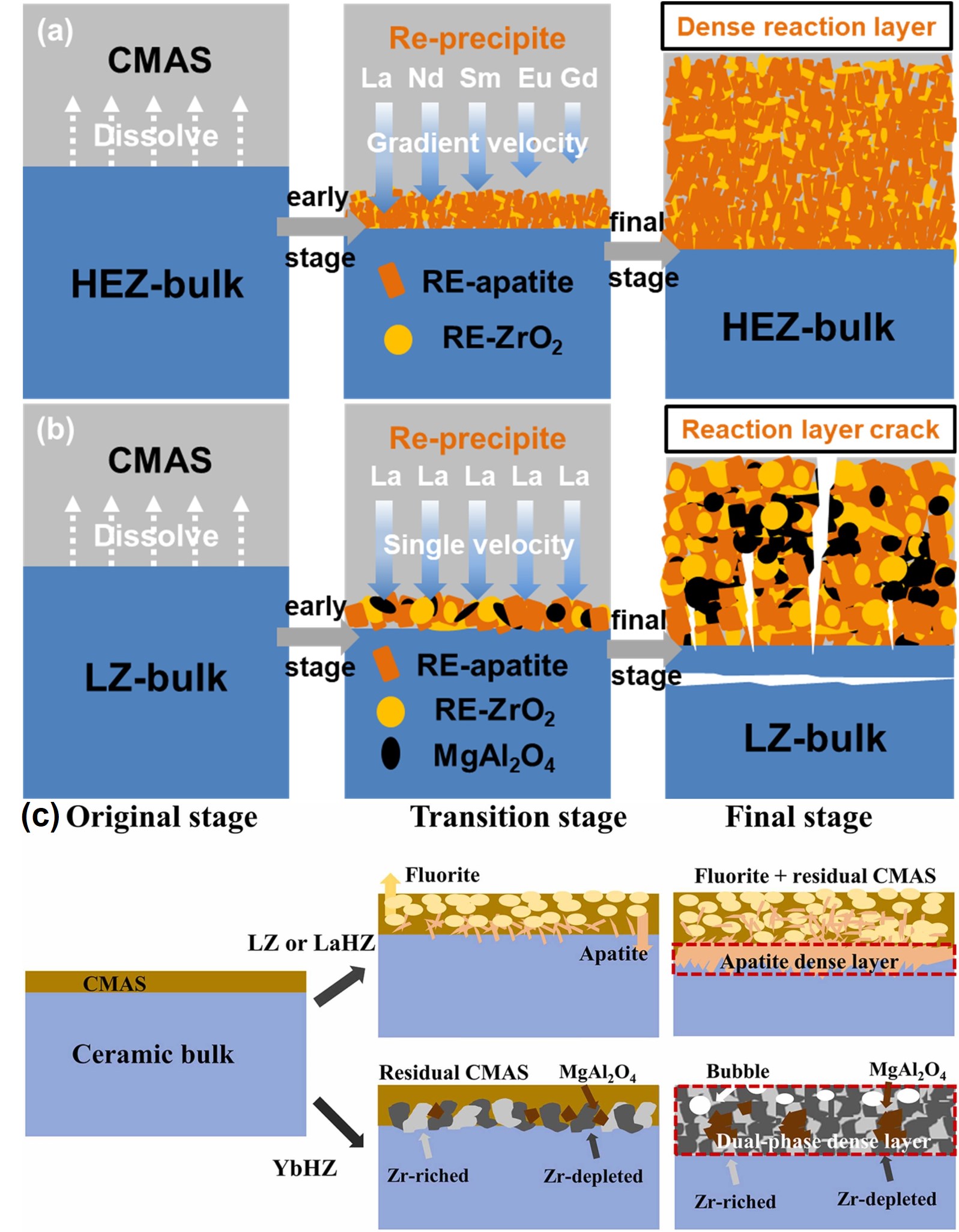

Fig. 43 (a) Collage of cross-sectional optical micrographs of β-Yb2Si2O7/1 vol% CMAS pellet that have interacted with CMAS at 1500 ℃ for 24 h. The region between the arrows is where the CMAS was applied. (b) Cross-sectional SEM image of the whole pellet from the region I. (c) Higher-magnification cross-sectional SEM image of the region II, and (d) corresponding EDS elemental Ca map. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [ Fig. 46 CMAS-induced corrosion in HEZ and LZ ceramics. (a) HEZ: Dense RE-apatite and RE-ZrO2 layer without cracks, exhibiting graceful degradation. (b) LZ: Formation of RE-apatite, RE-ZrO2, and MgAl2O4 layer with cracks, indicating reduced CMAS resistance. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [

Fig. 46 CMAS-induced corrosion in HEZ and LZ ceramics. (a) HEZ: Dense RE-apatite and RE-ZrO2 layer without cracks, exhibiting graceful degradation. (b) LZ: Formation of RE-apatite, RE-ZrO2, and MgAl2O4 layer with cracks, indicating reduced CMAS resistance. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [